Yaku Stapleton

Runecraft, Afrofuturism, an internship with Aitor Throup, and the term ‘couture costume design’ could all effectively describe Yaku Stapleton’s work and world, but seeing his clothing seems to eliminate these disparate references. Stapleton is singular; his work makes sense in the contexts but stands firmly alone as what Stapleton describes as “Sculptural, bright, sensory, textured.” It is a functional fantasy, a futurist cosplay for the every day, something earnestly nerdy and inventive. In Stapleton’s Central Saint Martins 2023 MA show, a purple puffer insect bag seemingly feasts on its green-sweetened wearer whose neighbor wears giant clawed monster boots. A pair of his newer Creature Shoes layer old sneakers with reused and dyed fabric, reforming the familiar in a bubbling, organic texture. Stapleton has a way of making the old feel not just new, but authentically futuristic.

Stapleton’s breakout CSM show won him the L’Oréal’s Professionnel Creative Award giving Stapleton the press to be stocked by SSENSE, Dover Street Market, and smaller London boutiques . His commercial success and acclaim are striking in a climate that has often relegated complex, custom, sci-fi/fantasy nerd-tech wear to tinier Instagram accounts. Stapleton has Bode-ified this market: synthesized DIY clothing practices (repair culture, larping, cosplay) and created dual markets for 1/1 customs and more replicable, commercial, everyday pieces. What distinguishes Stapleton from his Instagram contemporaries and endless “new“ SSENSE brands is a sense of personal lore and storytelling that weaves through each look and piece.

Matty Bovan

Approaching Matty Bovan’s twisting collages of tweeds and tartans, geometric twists, and ragged patterned fringes, one may discover what might’ve happened had Vivienne Westwood dropped acid with Rei Kawakubo. A Bovan show has an intensity, a mastery of a million tattered pieces, an untameable chaos lovingly wrapped into a street couture. Bovan has collected awards and acclaim since graduating from Central Saint Martins in 2015 and working with Marc Jacobs and Miu Miu, yet has rebuked subservience to the industry through a headquarters in York and a disregard for digestible/sellable garments. In fact, Bovan has been more active with galleries and installations than retailers - recalling a moment in fashion when a runway could feel more like a gallery than a supermarket.

Unfortunately, this dual focus means Bovan’s clothing can be hard to come by. I was not able to find any online retailers selling his work - yet another rejection of a fashion system in preference of slower, more realistic routes.

It would be unfair to say Bovan’s work is simply nostalgia for distant pasts - it suggests the renewal of an aesthetic for a harsh future. As Bovan reminds us, “More than ever, we need less stuff. Mass consumption, mass production can’t go on for ever.” The future of clothing is one of endless rags, acres of unused fabric, an excess that can be harnessed and never ignored. Bovan’s work is seen as dystopian/utopian by many because it is one of the few fashion fantasies to effectively embody and harness this inevitable truth.

Steve O Smith

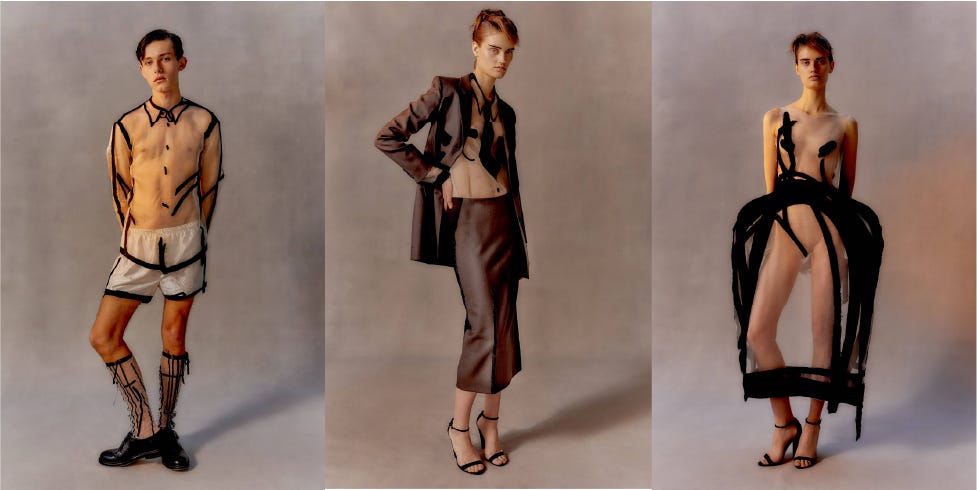

Steve O Smith has an e-shop, and on it are three garments for sale: a made-to-order suit and a mohair jumper, both with painted skeletal motifs. Seeing these sculptural, illustrative pieces one might google his name and find his sensational FW24 collection. Smith’s focus on the art of fashion illustration fused with George Grosz’s sketches of Weimar Berlin to create 17 looks that seemed as if they had been drawn onto models. Shirts, dresses, and gowns featured fluid black brushstrokes over sheer tulles and silks. Scribbles found their way onto endless scarves, skinny charcoal coats, and a ballooning wedding dress. It made Galliano’s Margiela Artisinal collection the year before look like a sexist puppet show; cold and unwearable beside Smith’s warmth and eroticism.

Smith has now been embraced by names as varied as Harry Styles, Cate Blanchett, Eddie Redmayne (for this year’s Met Gala). Most of these successes came after graduating from Central Saint Martins in 2022. Before that, he was attempting to sell wholesale with garments resembling a more commercial Westwood or John Alexander Skelton. These were beautiful clothes, still unique in their niche, yet clearly the pace and requirements of the modern fashion system were not benefiting Smith.

Smith’s switch post-CSM represented a focus on minute and specific craft and aesthetic, the fantasy and craft of made-to-order garments, and a general focus on slowness and refinement. Smith’s success is a testament to his ability to ignore and redefine the pace of modern fashion, and to craft something more meaningful and staying. Here, less truly becomes more.

Xander Zhou

A few months ago I stumbled across Xander Zhou’s FW24 show and was quickly dazzled. Zhou showed a staggering 69 looks featuring a robot-supervillain technocrat chic complete with menacing canes, capes, & frozen feline sidekicks. The show quickly found fans across Instagram and Twitter fashion circles for its sense of fantasy and scale, and by mixing a nerdy dress-up itch with luxurious chic. It might be a modified larping if the looks didn’t cling so effectively to function and normalcy. Forget a circuit board here, a pointed collar there, and it might just pass without a second glance. Zhou’s worlds encompass incredible breadths, unfamiliar regularities, and cultural crossovers.

Zhou is a Chinese designer, the first to show in London, who has been holding collections since 2013. Zhou defines his pre-2018 shows as “a prelude to a story, paving the way for future development.” Post 2018, his shows follow a linear movement and pattern of characters and motifs, tweaked and twisted to normcore basics and viral extremes. Perhaps a man will walk the runway seemingly pregnant, or with six arms, or holding a giant yoga ball. Each will feel like a natural escalation from the costumes of alternate futures, worlds of new strictness and fresh deviations. Zhou’s work is not quite escapist - it is preemptively subversive of whatever structures may await us.

Wataru Tominaga

Bright patchworks of picnic table checkerboards and fluorescent geometrics clash against 80s dayglo greens and 70s amber tracksuits meet me in the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. There are multiplied cartoon creatures, slinky crocheted dresses embedded with tee shirts, and shoes enveloped in straw. This is the work of Wataru Tominaga, presented alongside pieces by CFGNY in the exhibit “Refashioning “ which seeks to “challenge preconceived notions of gender and identity, and in particular what the artists describe as “vaguely Asian” aesthetics“To amplify and contextualize his work, Wataru hangs his garments on Ikou racks (traditionally used for Kimonos); each piece split as art object and commodity, genderless without model, refuting and expanding the sense of the looks as national. While this setup may imply garments that are overly conceptual or precious, Wataru’s work seems most preoccupied with the joy of expression and creation. A significant feature of the gallery is a room that will eventually be used by local artists to collaboratively create a giant patchwork quilt.

Wataru interior and industrial design before moving to study at Tokyo’s famous Bunka Fashion College, Design Helinski, and finally at London’s Central Saint Martins in 2015. The next year he won the Première Vision Grand Prize at the 2016 Festival d’Hyères which imbued his brand with cash, press, and a relationship with Chanel’s Metier D’Arts. Each of the tools Wataru has been awarded and his prolific international education has not made his work fussy or overly serious. Usually when clothing is called “art“ it is meant as a sign of unwearability - you can love a Giacometti sculpture but you wouldn’t want to live in one. In Wataru’s case, he uses the gallery as another stage for understanding wearable clothing - not pigeonholing it as one or the other. There is a radicalism to all textiles, all garments being understood as a craft worthy of being art objects.

I have returned often to Wataru’s SS23 vintage graphic tee shirt, its back embedded in a droopy caramel crocheted dress. In some variations, the dress is long enough to fit two shirts, in others the shirt is split in half, the front and back completely integrated into the dress. The result is reminiscent of Undercover SS06 (an easy association, it’s my favorite fashion show) and Martin Margiela’s modification of Takahashi’s fake band tees by cutting holes behind the tee shirt’s sleeves. When worn, the tee shirt is modified into a new art object as draped garment, but also broken down as a symbol: one is literally wearing the structure of a tee shirt rather than sitting inside of it.

Wataru’s version is far more egalitarian - replicated with accessible vintage and heightened by hand crochet. Wataru’s experiments are conceptual and experimental, but he roots each in an applicable historical context of wearability. For the crochet, he mixes the style of oversized tee shirt dresses with hippy-style crochet knits. There is a joy to the accessible intellectualism of these garments. They are inviting not just in that they are wearable, but as a feasible aesthetic and mode for sustainable patchwork, fashion constructed from deadstock and “used“ clothes, and DIY & repair cultures to enter more lauded artistic halls of repute and analysis. This is a carefree, almost incidental futuristic vision.

Ryunosuke Okazaki

At the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Sleeping Beauties costume institute exhibit is a spotlit dress of wiry black cords and sinewy tubes. It resembles a sketch for an early flying machine, or the bone structure of an alien bird. It is a dress from Ryunosuke Okazaki’s SS24 collection, a Tokyo designer known for his architectural and sculptural dresses of twisting geometries. His SS22 show was influenced by Jamon era pottery which used rope imprinted patterns, a practice that attatched the act of prayer to an object. For his FW22 show “Pray“ he adds that “To create is also to pray” which could explain a focus on “decoration [rather] than function“. Okazaki is from Hiroshima, and one of his earliest works was crafted from paper cranes (used as to symbolize peace) - a tactile example of object as prayer, and decoration as action.

For all the coldness one may associate with such jagged, sculptural structures and the galleries they seem to fill, Okazaki seems most concerned with the concept of his garments as affective objects. His work pushes against the idea that clothes one cannot wear do not have affective landscapes. Moreover, he reminds that there is value to the nonfunctional wearable dress, and that the ability for a garment to transfer emotional quality is itself a valuable function.

Mademe

I am late to Erin Magee’s MadeMe. The brand is a gem from the 2000s streetwear scene in New York, one of the few made by and for women. While serving as Supreme’s Vice President of Design and Production (a culmination of almost two decades at the brand) Magee has crafted MadeMe into a sharp streetwear powerhouse by working with Paul Frank, X-Girl, Stussy, and Dr Martens. Her muses are as varied as Rihanna (an early supporter), Princess Nokia, and Paloma Elsesser. The brand is essentially a homegrown Heaven Marc Jacobs, sans appropriation - a celebration of femininity in 90s to 2000s alternative culture. MadeMe may have less cash flow than Jacobs, but it lived the moodboard Heaven cribbed. For this reason, MadeMe does not need to collaborate with X-Girl or Hysteric Glamour to cite or embody it, Magee recognizes it is not the name but its subversive context that draws power.

I knew none of this context when I first encountered MadeMe clothing. I saw a streetwear brand perfectly primed for the era of quiet: faded denim carpenters with perfectly grayed camo knee panels. I saw ruffled Alpha Industries jackets that were both like Avant blousons and ruffled Lolita collars. I saw a sublime Paul Frank collection of leopard sweaters and bowling bags. What I discovered when I dug was a gloriously 2000s Stussy collection featuring Liberty London fabric-lined moto jackets and blue bombers. I found MadeMe’s trove of infamous reactionary feminist slogan tees that disrupted tabloids and ruffled more conservative feathers than any Supreme tee in recent memory.

In a moment in culture so devoted to the 90s “It Girl” in all its specificities, it’s inspiring to see someone able to replicate that feeling through a study of the “It Girl“ as character and design subject rather than literal “It Girls“ (Side note: Can someone be “So Julia” without knowing “Julia“? What if in doing this they are more Julia than Julia?) Magee has her finger on the pulse of New York nostalgia and chic alike, and MadeMe is a powerful manifestation of that taste.

Andrew Groves

Before Andrew Groves was a Westminster Academic he was a designer. Before that, Alexander Mcqueen’s assistant, and before that, the 90s fashion kid behind London club brand Jimmy Jumble. Groves would craft strange creations for drag queens and future models, from “fashion police“ coach jackets to sweaters with fried eggs printed over the chest that would invariably reach cult magazines and pop television. Between 1994 and 1996 Groves dated Mcqueen, assisting with pattern cutting and design for shows like “The Birds“.

Groves is notorious for two runway shows, the first being his SS91 “Cocaine Nights“ after the JG Ballard story & the movie Face Off. Models walked on a runway covered in white powder, faces encased by disco balls, fleshy masks, and a landscape of bruises. It was sheer, sexy, and in direct confrontation with the war on drugs. Even in the BBC’s review of the show, former provocations are recalled, such as his SS98 collection “Status“, which ended with Groves releasing of five hundred flies from a jacket. Less regarded is his FW98 “Ourselves Alone“ (a translation of the Gaellic Sinn Féin), which dealt with the Troubles through burning crucifixes, models on fire, and mixing “charred green taffeta“ with Protestant-Irish orange. Groves does not deal in easy clothes, nor simple pleasurable shows. He recalls the treatise of the old days being that “there being no point in dragging people to a show, unless you give them a show.”

Because Groves was active as a designer for such a short period, finding his clothing is both difficult and expensive. The legacy he leaves (besides a lengthly academic carreer publishing archives and spurring talent) is one that centers the institution and medium of the runway show. The lasting power of Groves’ work is that these provocative, performative runways are so evocative in spite of their ephemerality. Poorly recorded and without many garments in modern circulation, they remain as runway shows once were: whispers and myths, blurred snippets and a theater rife with subversion. It couldn’t be ignored, and I hope it isn’t today.

Kohei Makita

HECTIC and its designer Kohei Makita were brought up in an interview with two previous editors for Japanese fashion magazine Ollie when asked which Urahara brands were signficantly under-reported. All I had were these two names, and the fact that the brand was sold in a Supreme distributer called One Gram. Makita was actually the only name of the list that returned additional results, such is the way with the sparsely reported and now esoteric Urahara movement in 90s Japan.

An online interview yielded more: Makita worked for denim replica brand FULLCOUNT before being introduced to the One Gram team when questioned about Supreme by SOPH.NET founder Hirofumi Kiyonaga. After HECTIC, Makita began designing an in-house brand for One Gram called MOTIVE, which is cited as being one of the first Urahara brands to create incense holders (Neighborhood, WTAPS, Wacko Maria, and more all now sell incense & holders). MOTIVE shuttered by 2007, giving way to Makita’s longest running project The UNION (separate from the Union store, although Makita worked with them this year).

I realize much of this may ammount to nerdy gibberish at best. I’m fascinated by Makita and his work, not just because of my love of Urahara subcultural design and history, but because of how many aesthetics and experiments are lost in the greater successes of a Nigo (Bape) or Takahashi (Undercover). It’s inspiring to see not just how diverse these subcultural movements could be, how far their fringes could diverge, the aesthetics that could emerge from the same starting point.

SHOP THE DESIGNERS BELOW

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Hi and Lo to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.