I Am What I Wish For

Desire, Wearing, and Wanting

I think it's ridiculous to dress up in luxurious items and to obsess over changing into something different from your true self just because of an admiration for the aristocratic mood of the upper class."

― Are you suggesting that people should dress like themselves?

"To put it more simply: can you meet anyone in the clothes that you always wear? I often say, 'if the Emperor of Japan wanted to see me, I'd go dressed like this.' Does one believe that they could continue to dress like themselves in their favorite clothes no matter what they can encounter? I think this is the most important question concerning 'wearing'."

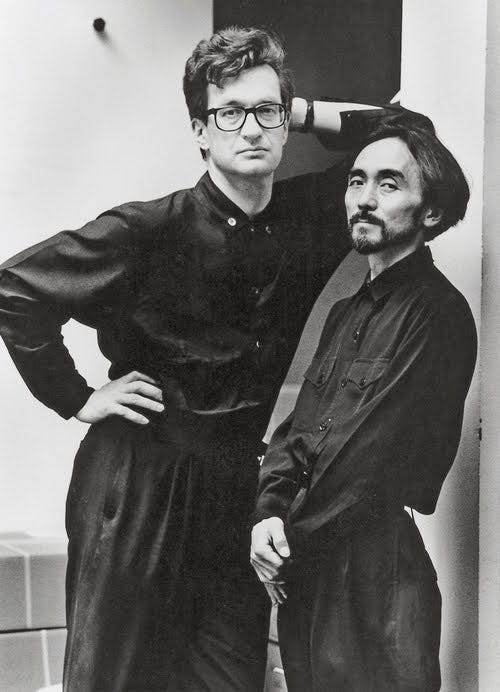

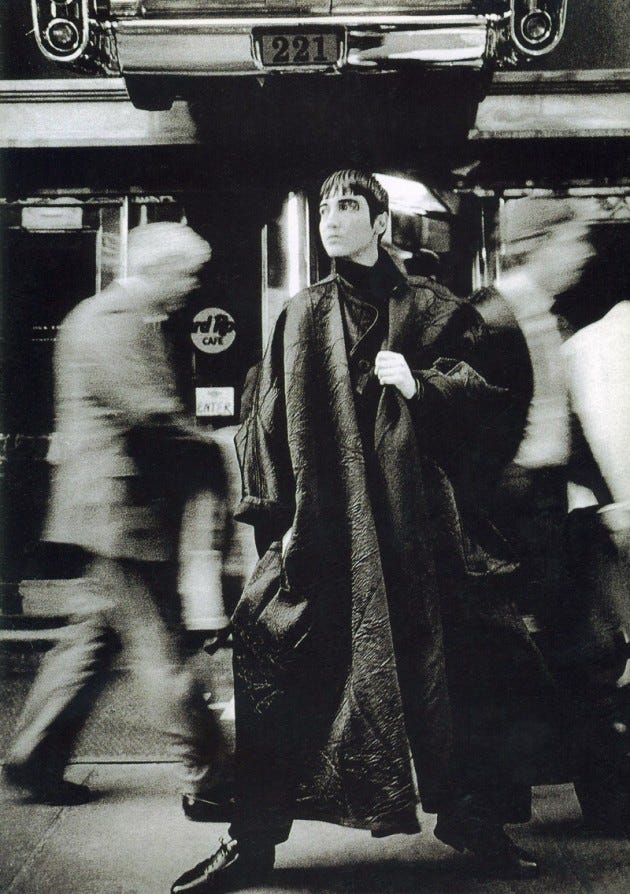

This is Yohji Yamamoto in a 1991 interview with the magazine Tokyo Calling. Yamamoto is a designer known for his charged aesthetics of dark and flowing fabrics, baggy and worn suiting, and fluid movement between formal and street. This work is a derivation of Yamamoto’s obsession with 20th-century clothing and its built-in communication of set occupation and unchangeable, sublime uniform. Yamamoto calls these “life” or “as-is“ clothes. Looking at his clothes, this is a philosophy that translates

There is beauty in Yamamoto’s sentiment that luxury can be denied in favor of a truer, more personal way of wearing. It’s easy to think that desire for luxury comes from a desire for status. However, luxury doesn’t necessarily refer to a price point. I’m sure many would consider one of Yamamoto’s thousand-dollar long black coats as “ridiculous” as an all-over print Gucci bag. Yamamoto’s issue is that people care about garments that have no bearing on who they are. In his eyes luxury is alien to the authentic soul and person, and any desire for it is the result of subservience or indoctrination to a manipulative society.

It’s a utopian vision. Everyone dresses to match their individuality beyond trends or Fashion. Without “society“ or “class“ in the way, we emerge with all the best and none of the worst of Yamamoto’s vision of 19th-century “living clothing“. Is this true dressing or real wearing? Is something missing?

The first fashion writing I ever attempted was about Martine Rose, one of my favorite designers. Rose is a British-Jamaican designer who predated and ultimately became famous for helping Demna establish his Balenciaga oversized silhouette, and has also existed on the periphery of the fashion spotlight through her fantastical warpings of modern English subculture. Her clothes are bold, sexy, and usually marked by one or two oddities or controversialities. No, those square-toed loafers are actually mules, yes that track jacket is supposed to bunch up at the top. It’s priced high, and perhaps too deconstructionist to be true luxury - yet Rose sits in the top three contenders for Louis Vuitton’s next menswear designer.

I love Rose’s philosophy of dress and the aesthetics she questions. It is the idea that normalcy can be achieved in concept but warped in practice, that sex can be everywhere, that we can play dress up and remain authentic, and that clothes are fun. I can describe this, or draw the concrete histories, references, and aesthetics in specific works by Rose, but it will all fall short. There is a connection I feel to this world, and a knowledge that seeing Rose’s work changes how I dress, feel, and think which makes writing about her feel small.

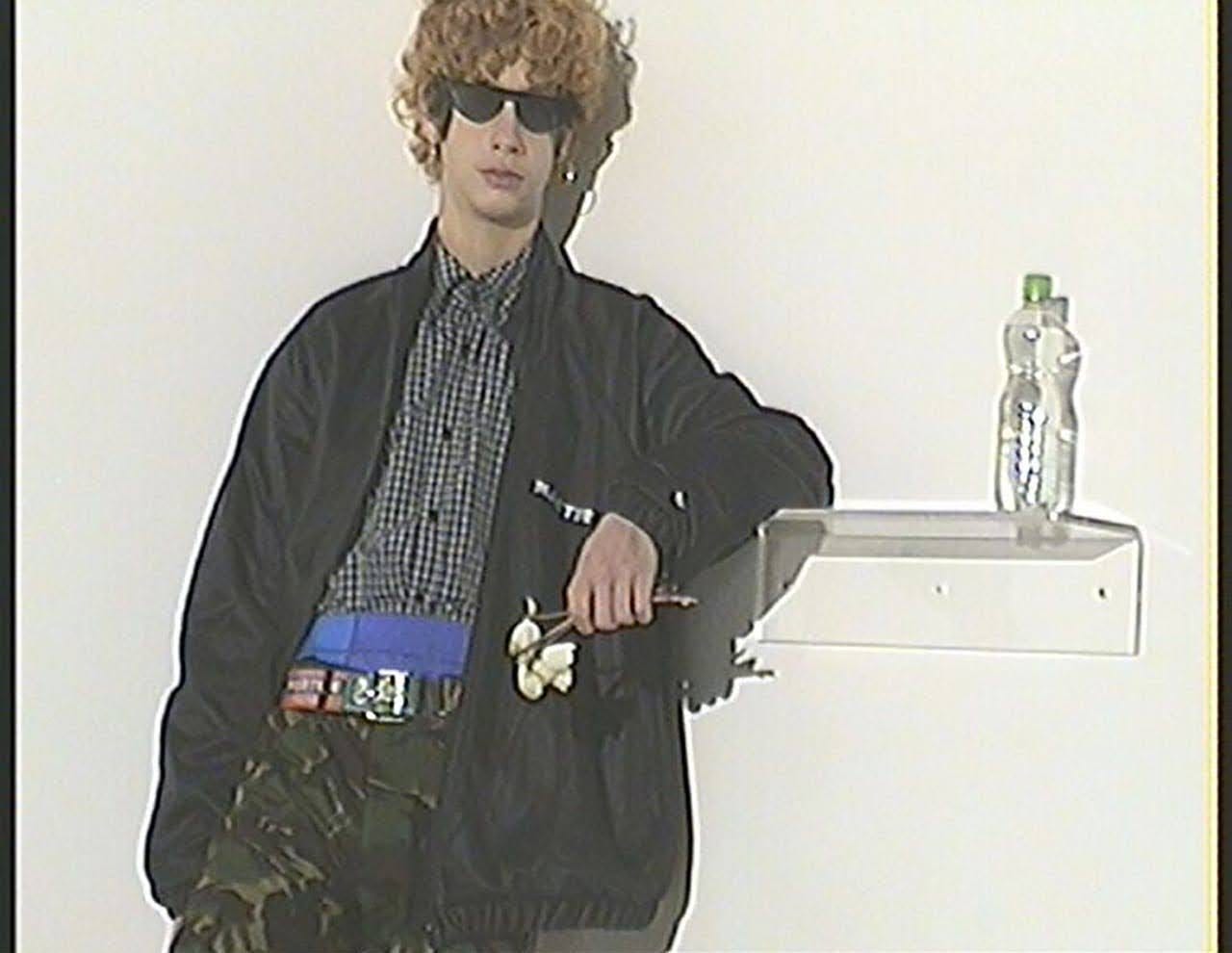

The first piece I ever saw of Rose’s was this piece from 2018.

When I first saw that fleece I dressed in an odd amalgamation of LA hypebeastery, poor vintage decisions, and imagined straightness. Soon I became attracted to Rose’s large leathers, odd denim recreations, and loafers. Soon large silhouetted blazers and undershirts, gorpy Nike, and flooded pants attracted me. Not all of this came from a stream from Rose to me, rather, they were there waiting for me to accept and understand. Rose’s work became like a guide and a friend, there for me when I needed it and always willing to question. What do you want? Why? Why Not?

Four years later, queer, obsessed with suits, and searching for flooded pants and UK house, I thank god that I am not frozen in the clothes I had then. I am thankful for the ability to grow into garments and out of them, to desire and stop desiring and create something different in the face of absence. I am grateful to have discovered clothes that feel so close to me that they are too tangled in affect to be described or explained.

As a smaller, philosophically minded independent designer Rose reminds us that wearing is not the only way to resonate with a designer’s work. One can experience clothing like a library, picking up and putting down ideas and only buying a hardcover multivolume library to that which is essential. Yamamoto posits a single philosophy person and garment, a unification of body and mind that eliminates time and desire. Steve Jobs in his turtleneck and New Balances, John Mayer’s all-visvim wardrobe, and even Ye in his Balenciaga-or-nothing wardrobe reflect the ideal that clothing can adequately bind and describe a person. But in all of these cases, there is an air of the constructed and the fabulously wealthy. Is this concept realistic? Would we want it if we could have it?

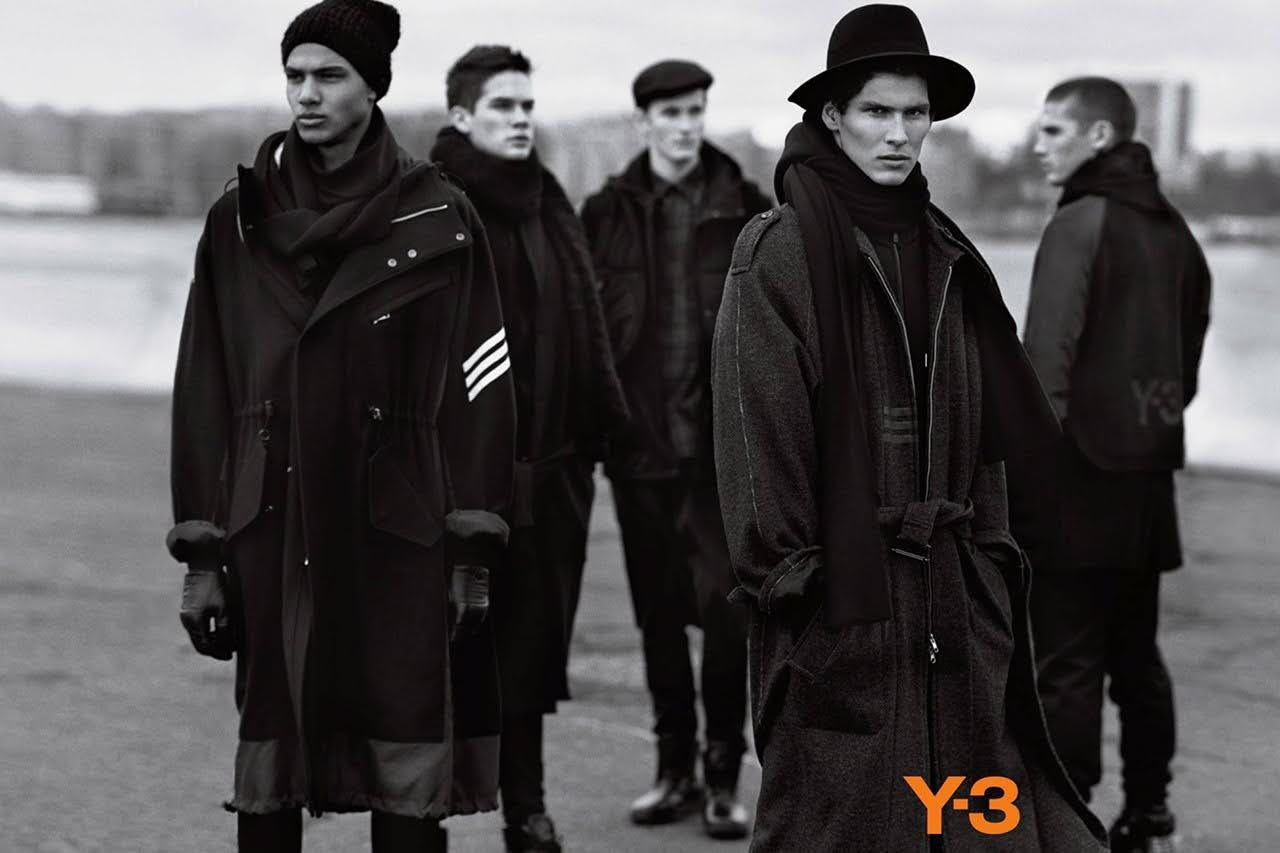

Years after Yamamoto’s interview he discovered something upsetting: he no longer saw people wearing his clothing. Yohji does not make clothing that is necessarily cheap or accessible after all, so in the 2000s Yohji established Y-3 with Adidas as a less expensive alternative. These garments did not resemble turn-of-the-century coats and flowing workwear, they were technical, bulky, and futuristic. It was nylon and heavy branding - true sportswear. Compared to the rest of the market at the time, this was the closest thing there was to luxury sportswear.

What is a book if it isn’t read? What is a garment if it isn’t worn? How can one come to wear a garment if they do not desire it? Y-3 isn’t a selling out of Yamamoto’s decrying of luxury, it’s an admission that the philosophical is intrinsic in the garment. Y-3 is a check against the statement that luxury exists solely as class delineation - it can, but that doesn’t erase the fact that luxury clothes are just as philosophically bound as any other. Moreover, the narrative of Y-3 centers the importance of seeing clothes work in the world.

The philosophies of Yamamoto or Rose do not benefit from being stifled by becoming static uniforms and perfect descriptors. These clothes, all clothes, grow more meaningful when they can be mixed and matched, desired and disappeared, and subject to the changing whims, bodies, and souls of their wearers. Perhaps perfect, unchangeable clothing is as achievable as a perfect person. All the better.