I am an obsessive of Jun Takahashi. I can’t even say it’s because I love his brand Undercover because of how much additional love I have for his side projects and predecessors such as A.F.F.A, Gyakusou, John and Sue Undercover respectively, as well as The Shephard, whose blazers and coats keep me up at night dreaming of old age. After thirty years of work Takahashi has not slowed. His men’s collection for this coming fall, a Psycho inspired romp through denim printing and mohair Hitchcock worship piqued my curiosity when I saw its static lookbook, but for the first time in ages I found myself more drawn to Takahashi’s vision for fall womenswear. He mixes leather dresses replete with zippers with odd and oversized gold jewelry as well as a host of bizarre leather jackets presented in metallics and distorted silhouettes. It was the stuff of fantasy and obsession, of dark lights and heavy eyeliner, murky red furs, and bejeweled tartans. Watching this show was like hearing the retelling of a dream, of watching a man return to his roots and flex both knowledge and mastery of punk style.

I still do not know how I discovered Takahashi, but it probably had something to do with my own obsession with punk and its graphics. It did not take long for me to learn Takahashi was a Brit-Punk obsessive, leading a Japanese Sex Pistols cover band and collecting Vivienne Westwood’s Seditionaries so obsessively it warranted its own book. Takahashi’s work fueled his punk fixation for years, with standouts such as SCAB, DAVF, a Patti Smith collection, and more modern flips of graphics by CAN, Television, and the Ramones. In a world where a vintage punk t-shirt can cost thousands and Vivienne Westwood remains steadfast in the world of couture, Jun Takahashi felt like the most authentic voice speaking to the subcultural niche graphics and philosophies of punk.

It wasn’t necessarily that Takahashi was any sort of punk purist, rather, his designs came from a place of authenticity and earnestness. Just around when I discovered Takahashi he was leaning into an era of unabashed film-bro nerdiness, with reverence directed toward Kubrick twice, Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood, and now Hitchcock. Even before this more dramatic switch, it would be unfair to label Takahashi as a purely punk designer; he has ventured into the worlds of fairytales, the pastoral, the Anglophile, the comic book, and graffiti.

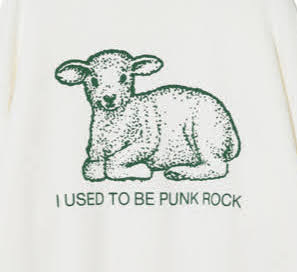

Even in knowing the versatility of Takahashi, there was something completely amazing about wandering through Dover Street Market (in my Undercover Converse of course), flipping through the giant gold safety pins and golden motorcycle jackets woozy with the idea that the, if not my, king of Japanese punk wears was back. Then, dangling off the bottom of the rack I saw this:

“I USED TO BE PUNK ROCK“ with an eyeless lamb sitting peacefully, staring blankly out into the world. A slouchy black sweater, white, black, or red, in women’s sizing. The last descriptor is insignificant if not for the fact that the sweater then belongs within Takahashi’s Women’s ready-to-wear, sold alongside the leather jackets and zippered dresses.

“I used to be punk rock”, past tense and all. Humble? Self Aware? It’s just too blunt and graphic to be properly ironic. And yet I think Takahashi means it.

On the note of cultures of leather fetishism, I recently visited the sensational Tom of Finland house in Los Angeles, the old abode of the gay erotic artist and living archive of his work. It’s a dizzying experience, for a queer person at least. The house is run by Tom’s muse and lover, tours given by aging leather daddies, and penises of all sizes, cuts, and mediums riddling the magnificent craftsman house. During the time of Tom of Finland’s work, many of his illustrations had to be mailed to order and fashioned in outlandishly small sizes. To encounter these works that glamorized not just the fit male body but the leather uniform and motorcycle had a tremendous ability to influence both style and self. On one hand, someone could find solace knowing they were not alone in their gayness by looking at Tom’s work. They could find solace in leather too. Some would go to tailors with Tom’s drawings requesting similar cuts and shapes as those he had concocted. During the tour, it was mentioned that as Tom drew Danner police boots with varying straps and shapes, it would seem as if the company would respond by producing new models based on both his illustrations and the demands of his readers.

Between new mediums, success, galleries, and devotees, the AIDS crisis hits. Tom’s first thought as he watches the impact on the gay community is that his work has only promoted the free love and sexual abandon that has fueled the death he was witnessing. He swears off illustration. A master in his craft and confident in his abilities knowingly stepping back.

Eventually, as our tour guide recounted, Tom met a friend dying of AIDS who urged him to return to his work. The art Tom created was about the celebration of vitality and life, itself an image of the vital and powerfully human amidst the destruction he witnessed during World War II. And so, Tom returned, but differently. He crafted deliriously sexy condom ads and incorporated images of safe sex into his work. Later, his work veered into tackling racism within gay spheres. Already one who depicted interracial gay relationships as early as the 40’s, Tom began a gargantuan unfinished project completely devoted to black subjects. He was continuing to create, still using the same muses and models and philosophies and fetishes, but with purpose. Instead of his aesthetics barring him from the future, he accepted the place and power those aesthetics have in the future. He grows, knowing he is more separated from the world he depicts, yet no less capable of crafting it.

My favorite Tom drawing that illustrated this shift depicts three of his muses in typical uniforms, leathers, and washboard abs. They gaze out at the viewer with a quiet kind of intensity, framed not by typical bright and full Finnish forests. Autumn has come. The background is dark, sinuous and beautiful, but unmistakably bare. Tom has returned to a world of gorgeous men, powerful and alive, yet under a new inescapable context. Times have changed. When the homogeneity of Tom’s work changes so largely, and in such pointed ways, their power only seems to increase. In Tom’s fixed world of youth and sex, they will only truly change if they must. And they must change.

Takahashi’s collection, alongside Tom’s post AIDS illustration, tell us time has changed. Takahashi’s jewelry is exaggerated and faces cloudy with shadow, Tom’s now somber men somber emerging from ambient darknesses because both are being warped through memory and time. And yet, both are marked by the hands of an expert; the former members of clubs that are irrevocably changed. Neither development means the artists have disengaged from the subcultures they exist in, merely that they have changed.

Old punks and gays, and sometimes both in the specific case of John Waters, often complain at the lack of modern subcultural identities. “If your kid comes out of the bedroom and says he just shut down the government, he should have an outfit for that.” he proclaims. While as an obsessive of various subcultural heydays I understand the aesthetic critique Waters offers, I also find a beauty in the destruction of these old barriers. Authenticity is not simply the ability to follow sartorial instructions. Craft cannot be relegated to the reproduction of what is known.

And yet, obsession is powerful. Tom’s repressed lust inscribed into every muscle of his men, the exactitude of one of the Seditionaries references in Takahashi’s early clothing spoke for themselves in their ability to serve as a beacon to the similarly obsessed. What Takahashi’s new sweater reminds us is that the subcultural label does not power obsession and passion, but vice versa. What is the denial of a label or a format but the freeing of ones self to truly explore?

Seeing Takahashi’s sweater set me free too. This was a sweater, though simple, that held memory and power in it’s black thread. It was hearing my dad talk about avoiding OC skinheads and catching the Clash at the Coliseum. It was me stumbling through Camden and watching the still stiff mohawks and dusty leathers roll by. It is proof that our present is nothing if not memories, disidentifications, and old allegiances. And perfectly, Jun Takahashi’s declaration of being a past tense punk only solidified a consistent and murky devotion to the designers work. Free of label or subculture.