Inside Out

Dress Me in Uniform

I almost never had to wear a uniform, and I’ve recently decided that this is tragic. On childhood sports teams I wore the itchy jerseys and slouchy PE uniforms as long as I had to, but I was never forced into the strict garb of Catholic schools, boarding schools, Boy Scouts, or even a subconscious subcultural dress code. In the working world, namely, the luxury department store where I work, I’m beholden to a kind of “fashion“ business semiformal. It is supposed to be neutral yet elevated, personality is allowed but not to any extent that would preemptively end a conversation. We must depoliticize ourselves, homogenize uniquely, share brand loyalty, and more, loyalty to the cult and culture of luxury.

This uniform is ultimately a request to perform class, to feel comfort in and with luxury, to make oneself elevated from “average” and to appear to do so effortlessly. Faking is allowed. Almost everyone wears Zara, H&M, or Uniqlo, so long as it is labelless and assimilable. Sneakers are a particular favorite kind of paradox: fashion sneakers are allowed yet others are not, but what defines a sneaker’s relation to fashion seems contextual if not purely subjective. Moreover, a Dior “fake“ of a run-down New Balance may be accepted while the “original“ is not.

It’s often highly gendered as well. In the old days of this store, women were required to wear skirts and heels, while men usually dressed in suits. Nowadays, women can wear suits, shorts, etc. whereas men can wear skirts, but not shorts. Much is unspoken. We may present authentic interpretations of our gender, but anything that could get us kicked off the Bank of America pride float is a no-go.

The uniform implies that through its magnanimous broadness, we may find and then express an authentic self. More generally, it is assumed we can be easily molded to become “safe“ for work. However, what happens to those negotiating the boundaries and binaries of class, gender, and consumption? One coworker defines their uniform as “work drag”, in which “passing” is performance and skill. This perspective sees the uniform as a dance between conformity and slight loopholes and confusions that challenge the rigidity of the uniform’s systems. These challenges can get subtle, so subtle they become solely personal and otherwise inscrutable. I suppose that’s all one can hope for in a corporate bureaucracy.

Certainly, this uniform attempts to convince you must reshape your wardrobe around its barriers - how obvious that the dress code of luxury fashion wishes for you to consume it. And so I’ve been buying more clothes, used, of course, to satisfy this beast, and to find items to keep myself sane. I search for “luxury”, yet not, assimilable, rooted in myself.

During this time I’ve called perhaps even more deeply in love with Martine Rose’s work. She is an obsessive of subcultural uniformity, their breakdowns, similarities, and everyday applications. She’s explored the intersection between queer dress and business wear frequently, from her warped button systems on oversized shirts and suits, the rings and zippers she places, her use of lingerie as outerwear/mid layers, and her use of leather.

This season I encountered a silky iridescent shirt in a nutty brown, the sleeves more of a purplish grey. On the left breast of the shirt is a pocket with a triangular button flap, a black tag with “Rose Martine” embroidered in gold, and a similar gold-on-white tag below. The effect is something like an inside-out set of ornate pajamas, or 80s disco era top. Wearing this shirt inside out would then reveal the brand’s classic pink tag at the neck, creating the most obvious signal that this is a modern fashion item.

It’s oversized, meaning when worn it gives the effect of a partner’s shirt being picked up after a debaucherous night and thrown hastily on. It is silky, sexy, yet adaptable with a suit or layer, the signals that mark its explicit subtext made hidden.

It’s a shirt that doesn’t care how you wear it, that looks wrong no matter what, and feels good to wear

I’m reminded of Rose’s take on clothes designed without gender in mind as ineffective in their unsexiness, and the ability for clothing to become powerful through the push and pull of gendered aesthetics and tropes. This shirt is illustrative of that philosophy: a men’s cut with traditionally feminine fabrics, a fit meant to resemble an oversized look as worn by femme but designed for masc, and the way that looks evokes a specific gendered scenario referenced even more clearly by the inside-out design. This shirt is for a work drag that walks the line - just inconspicuous enough to pass inspection, able to implicate enough to raise an eyebrow.

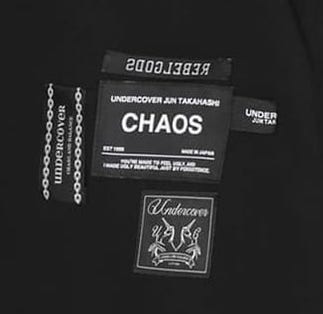

Poring over this shirt at Dover Street I found it had a strange twin in Jun Takahashi’s Undercover - a series of coats, blazers, and shirts in more traditional black hues, normal fits, and sturdy fabrics that had around its breast pocket not two but four different “undercover” tags. The tags reveal a more subtle commercial aspect to the inside-out shirt, here highlighted solely by Takahashi. Here, the tags sit sideways and upside down, feasibly homemade like a patch-laden jacket.

The tags reference different slogans, characters, and aesthetics from Takahashi’s almost thirty years with Undercover. Grace, a furry doll sculpture-creature of Takahashi’s design inspired a 2009 runway collection of ethereal milky white dresses, appears above the white unicorn tag. REBELGODS combines two words Takahashi has used frequently, and Chaos/Balance has been featured everywhere from Takahashi’s Dr. Martens, to leather jackets, and rubber rain boots. The unicorn tag, along with the chain tag speaks to times when Takahashi used more ornate and traditional symbols and aesthetics in his tags to reflect new materials and associations (punk, European craft, minimalism, etc.). Each of these worlds is and is not the Undercover of these garments - by design they are greater than the sum of their parts.

These tags, assembled together in a kind of “balanced” “chaos” recall an era of punk that relied on personalization through visual assemblage - patches, pins, rags, and the recognizable combined to send an ordered signal of self. To the Undercover obsessive the shirt becomes a more articulated expression of everything the brand has been - an opportunity to subtly access different worlds of the brand without the barriers of money or rarity. These tags reference admittedly unpopular eras of the brand because popularity or ability to associate isn’t the point. It’s about a complete story, about being able to question the patch/piece of the message you miss. The visibility of the tags in areas that reference the location of inside breast pocket tags creates the metaphor of the garment/brand examined thoroughly (inside and out) and revealed.

Compare Takahashi’s effort to Demna’s at Balenciaga:

Demna’s makes the logos large, and each one features the brand’s full name. They are organized chronologically and legibly, employing the most recognizable and viral of the crop. The chaos exists solely in the combining of these disparate worlds, but are ordered so to be seen. Demna advertises every popular iteration of his Balenciaga, but at the bottom line, it’s about the visibility of the repeated word: Balenciaga.

This is an excellent example of the disparity in how logoism can signal status and/or deeper meaning. On paper, Demna’s example does everything Takahashi’s does: placing symbols from a designer’s label in conversation. In Takahashi’s case though, these symbols represent Undercover in sometimes obscure ways, and are certainly not designed for legibility. Each of these items is otherwise inconspicuous - a “staple“ piece for easy wear. One logo piece exposes multiplicity, the other exposes itself in as many ways as possible. One brand peddles in money and publicity, the other in cult knowledge and nerdiness.

Takahashi is attempting to make his brand more than a name but a story, an aesthetic, something that can be personal and revelatory to us on our bodies. It is a puzzle to balance branding ourselves with telling our stories.

At work last week I saw a seller on the floor wearing a cropped blazer backwards. He sighed, lamenting that sometimes one had to change their look to deal with the monotony. It was the suit jacket his father had worn to his Bar Mitzvah, cut short with scissors and flipped around like a straightjacket. I was so ashamed to have thought it was Maison Margiela.

There is a tension to the rigidity of uniform. This is the tension that makes Martine Rose's shows so sexy, so wrong, and so bizarrely utilitarian. This is the tension that gives Takahashi’s concepts history and complexity. It is the rigidity that wore on my coworker until he found a way to wriggle through it into an expression of himself that undermined yet supported the uniform’s structure. I want to learn how to do this, to warp this new uniform into an expression of myself.

Well, I never wore uniforms much, but luckily I did read queer theory. Robert Munoz, in his book Disidentifications, describes a way of establishing one’s sense of self not through the binary act of “identification“ with a subject, but through accepting the limits and lack of that identity. This becomes a way of incorporating and identifying non-normative queer people who don’t see themselves represented within queer labels or identities, namely people of color. Munoz explains this model by turning the definition of queerness on its head, writing

One possible working definition of queer that we might consider is this: queers 'are people who have failed to turn around to the…interpellating call of heteronormativity. (...) we are continuously hailed by various ideological apparatuses that compose the state power apparatus. No one knows this better than queers who are constantly being hailed as "straight" by various institutions-including the mainstream media.

We can fashion ourselves through that which we are not, label by eschewing or reconstructing the label, and challenging the intrinsic political undertow of these rules. This speaks to more than simply a considered and thoughtful form of consumption - it is fighting back against any opportunity to allow our dress or ourselves to be politically warped into conformity. In other words, a work drag that is as cutting in its passing.

Can this be done with a brand? Can a vision overpower the visibility of a label? Can we twist gender and challenge luxury consumption and express ourselves and follow the rules? I hope so.

I love disidentification because it is a model that allows one to dream. It pushes against normativity, against complacency, and is ultimately a bettering force. Sitting unhappily in my work uniform makes me dream of this powerful drag, of one day, constructing its foreign boundaries, of becoming what this place is not.

Ben If you ever get the chance to visit the Balenciaga museum in Northern Spain you will love it. The couture is absolutely timeless and it is probably one of the most brilliantly curated museums I've ever been to.