Invitation Declined

"Losing your Voice" as a Critic, Gaining One Via the Outskirts

Is a fashion week invitation worth losing your voice over? Our field considers an invite the ultimate marker of success, a sign that your career is going well – but who is really benefiting here? After all, every invite comes with the expectation that you’ll contribute positively to the brand’s image. Most of us consider it a fair deal: access in exchange for loyalty. The mainstream media outlets create celebrity-focused viral content to gain the attention of their audience and please their advertisers. The independent writer showcases their gratitude and amazement in order to solidify brand relationships and gain credibility. For all players, the invite is considered crucial in getting what they want. The problem is that the content created in this ecosystem is entirely ephemeral. It’s fun, certainly, but what happens to a culture industry whose output has no long-term relevance? And more importantly, what happens to the producers of that output (the writers and opinion makers)?

We see content creators work hard to build up an audience and a voice, only for it to get diluted once they gain access to FW. These are writers who analyse our field and its cultural products with intelligence, integrity, and wit, often based on their personal values (such as race or class inequality, for example, or environmental awareness). Is the IRL fashion show experience really as valuable as their opinion? From our point of view, it is not. For writers today, a strong voice is their most powerful asset. We should all think twice before giving it away.

One can only criticize what they can consume. How can one write about a painting they haven’t seen, or pull apart a song they haven’t heard?

In the case of most visual art, film, and literature, the critic experiences art in the almost exact same method as everyone else. The setting or occasion may shift, but the work is identical. This is not so with more frenetic and “live” mediums like theater, food, or dance, where ensembles, spaces, and the quirks of artists become as legendary as they are impossible to replicate.

Fashion’s place in this group of mediums is ephemeral. The average person in 1970s New York could have never seen a Saint Laurent couture show, but likely saw a department store copy on the street. While fashion shows began as an intrinsically class delineated (if not completely trade focused) event, very few shows today are primarily concerned with their physical, immediate response. What brands vie for, beyond simply profit, is that which is most seen and reposted. The goal is no longer a precise announcement of style rules and hemline placements, but complete media saturation. All press is good press.

The fashion magazine is one way of crafting a new reality for the fashion show via curated inch-long slivers. As the most popular/ist mode of consuming the fashion show, it changes its reality, longevity, and understanding. Arguments over the modes of translation (digital v physical, publication, etc) spark other debates. Can one who receives gifts from a fashion house critique one of their shows? What if their magazine relies on their ad revenue? These questions reveal the paranoia of bias in fashion journalism at its highest level.

Herein is fashion’s critical oxymoron: complete access to a show is granted to those in the most prestigious critical positions, but what they criticize is vastly different from the digital versions of those shows the masses criticize. There is a knowledge of a live event that occurred, but the digital iteration of the show becomes a new reality for it to exist - and the one most everyone accesses. Does criticizing a fashion show mean as much when the experience is less “real“ than its digital iteration consumed by millions? Which medium of the show should be consumed? This is to say, if a critic reviews a showing of a film that is then completely re-edited for the public, what use is their review?

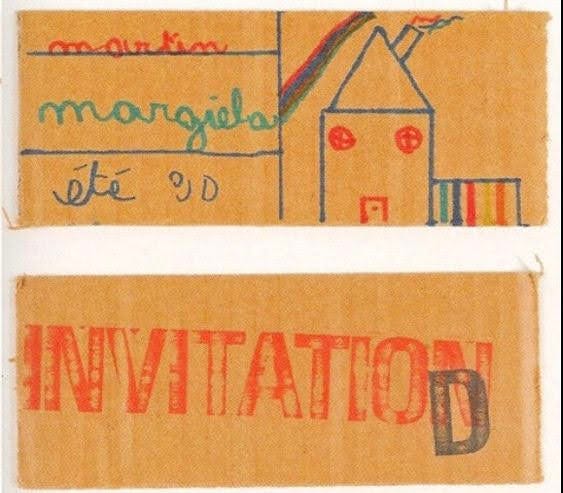

These are questions 1Granary approaches in an Instagram post last week, also posted above. The dynamic described is as old as David and Goliath: megacorporation versus opinion, monoculture versus niche, macro versus micro.

Ted Gioia uses the latter formulation when discussing the world of film, in which macroculture titans like YouTube and Zuckerberg's social platforms rely on independent niche creators for revenue; revenue which adds up to rival the profits of titans like Netflix. However, while these titans have found ways to make money off of nicheness, Gioia notes the various modes of censorship and limitation within these services. So, Gioia predicts war, and one the microculture will win. Below, he outlines the terms:

The microculture is the source of all the growth in media.

It’s already the source of most of the revenues.

Growth at many alt media outlets is still accelerating, so the gap between macro and micro factions is going to get much, much wider.

Alt media has huge influence on the public in ways most elites can’t even begin to grasp—because they operate in an echo chamber that shuts out this reality.

This alt audience is forming into actual communities with a surprising degree of cooperation and solidarity—which amplifies this emerging power.

Every round of layoffs at mainstream media creates new entrants into alternative platforms. The old guard is inadvertently training and launching wave after wave of new competitors.

But here’s the kicker—even the biggest potential enemies of microculture (those billionaires in Silicon Valley) need it for their own survival.

In Ted Gioia’s proposed war against macro and micro-cultures, micro will prevail in fashion for its ability to know the digital fashion image better than anyone. Moreover, they have access to and curiosity for a landscape of digital fashion images (archives, scans, histories, etc). Beyond a manner of perspective, is a more ethical niche these voices fill: to those not invited to (although invested in) high fashion shows, the conundrums of bias in invitation, gifting, and fandom do not exist in the same way.

A pause from fashion optimism for some sourness.

Last week one of my favorite critics, one I’ve always found strikingly honest and moral, called one of Fashion’s most notorious antisemites “sempai“. “Sempai’s“ show was deemed a return to a level of quality, beauty, and subversion unseen since the nineties - a proclamation made mostly by critics whose golden years were also in the nineties. Cathy Horyn wrote that the show was “a reminder of what a prison the luxury industry has become.“ In this sense, escape from the prison is not the future, but a rosy past.

In describing the show’s reach, many articles have featured soundbites of the young writers who missed this era and enjoyed the show for its ability to help them re-live a point in history they missed and yearn for. Social media mimics and dulls this point with the endless recreations and inspiration pieces the show has inspired.

On the other hand, as Vanessa Friedman puts it, While I can understand the desire for something you think you missed, I wonder if, in celebrating [this] “return to his roots,” we haven’t somehow missed the point. That era was also full of abuses (as the #MeToo movement uncovered) and self-destructive behavior. If we know this past being recreated is tainted, who will be there to challenge it? Will it be challenged at all?

Apparently, our “sempai“ considers himself one of the original victims of cancel culture, and will be releasing a documentary next month profiling this incident. Unlike some of cancel culture’s “victims“, like Louis C.K (Grammy winner post-cancellation) or Dave Chapelle (next Netflix special incoming) this man was “canceled “ by a court of law, and was appointed creative director of a huge fashion house three years after his bevy of violently ignorant outbursts.

Invisibility was this man’s curse, and in return, he was allowed to create. He made a then futureless brand corporate and profitable through ironic transfigurations of its subversiveness into luxury conformity. He revealed that an industry that will buy from abusive bigots so long as the hand of their direction is punishingly invisible.

A decade later he has decided he has done his time. So, his aesthetic returns in a shocking ode to past extravagance, and valuable criticism is nowhere to be found. Do we, the fashion buyers and viewers agree that ten years has washed away these sins? Perhaps in his appointment is the revelation they never cared.

And so, at the latest show is the crowd of celebrities, influencers, fans, and hungry buyers. To be invited to witness this show, one must not publicly criticize his decisions under the brand, nor call attention to his antisemitic history. The only ones who might be outright about critiquing the idea of this show in 2024 were not invited.

What do we do with “bad“ clothes?

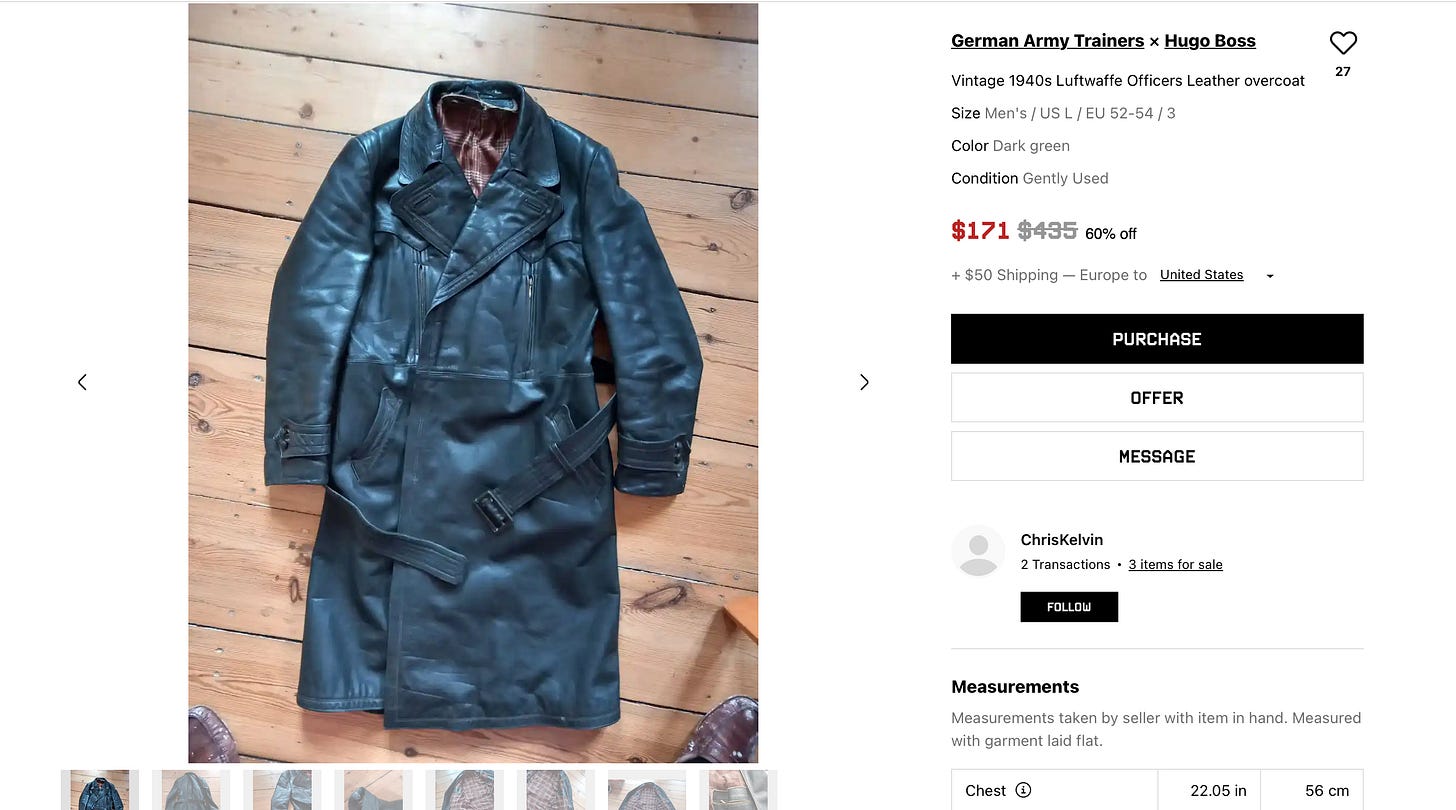

What do we do with that made be the reviled, in bad taste, or evil intention? What of the small evils, the endless disposable fast fashion worming its way into used clothing stores for decades or the stuff of fossil fuel dependent materials? How do we ferry these complicated pasts into the future?

This is a topic I’ve found fascinating and repeatedly relevant from 2022’s compounding Balenciaga/Ye scandal to the more recent fur debates. In a culture constantly reimagining itself through collages of pasts, aesthetics, and trends, the afterlife of clothing matters. What is in fashion from the past casts an enormous influence on what is seen and made, from sneaker retro models to who a celebrity chooses to collaborate with. The past, however, is rarely as newsworthy as a fleeting Tik Tok trend.

Here is a site for which Gioia’s binary of micro vs macro works in favor of the vast niches of vintage fanatics, fashion archive sellers and bloggers (each with their own specialties), and mood board pages. These are the voices who advise brands as curators and specialists, have dedicated audiences, and have received minimal special interest stories in macro platforms. Reckoning with the fashion archive is a daunting and inevitable task, particularly in the face of climate catastrophes and “uncertain futures“. Those most equipped to do so are of this niche class of micro-cultures, not those sitting in the ranks of a Chanel show.

I started writing about fashion because there were gaping niches in the study and writing of this complex, ever-evolving archive fashion world. It is the beacon designers have begun looking to, both for inspiration and aspiration. Moreover, it presents an ethical transfiguration of clothing “brought back“ into meaning from dusty obscurity.

As we approach New York Fashion Week and a new gauntlet of shows, spectacle, and discourse, we will see a bit of everything in miniature. There will industry self congratulation and proposed trends. Indie designers will present gorgeous new garb for their cults while publications wonder if anything new is out there. Archivists will point out references, stylists will pull related ensembles, and sellers will wonder if prices may rise.

But within these dynamics, the pushes and pulls between niche and mainstream, macro and micro, invited and homebound, is a war perhaps already won.