The passing of Issey Miyake has sent shockwaves through the fashion media this past month, spurring a broad range of memorializations. Most outlets with a stake in the art world or audience provided a comprehensive career rundown replete with quotes on philosophy, personality, and ethos. I suspected, however, that these articles were mostly being read by those already familiar with Miyake, and those on the periphery would see only the headlines and the Instagram posts. In this realm, Miyake took on fewer dimensions, relegated to the niches in which he was presented.

Curators and publications alike posted stills from his 2002 documentary Issey Miyake Moves or famous advertisements for his clothing shot by Irving Penn. To these sources Miyake was an artist-philosopher, wielding garments pleated and twisted with meaning and utopianism. More mainstream sources agreed with this claim, but focussed on the power imbued within one specific garment Miyake created, and in some headlines pre-empted the news of his death: Steve Jobs’ turtleneck. This was the object, ingeniously simple and culturally iconic, that all could understand as evidence of Miyake’s brilliance. When the hypebeasts and cruder archive fashion hounds recognized Miyake it was through their own lens of clout. What were his rarest garments, who wore them, and how did their cost change? Most circulated in these accounts and groups was a caption-less photo of Robin Williams at the premiere of Flubber wearing a tightly zipped 1996 Autumn/Winter Issey Miyake bomber jacket. Miyake’s face becomes rare among these pictures of his clothing, the proclamation from high-end retailers that his pleats are still for sale. Is this an acceptable or normalized form of commemoration?

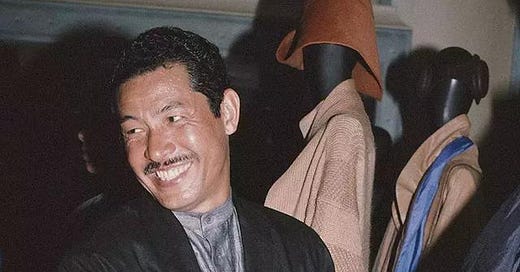

Of the first wave of Japanese fashion designers recognized and accepted by western audiences, Kansai Yamamoto was one of the first of the first. His death, and contemporary Kenzō Takada’s in 2020, yielded a media reaction that honed in on these figures as intellectuals, craftsmen, and shatterers of precedent in a similar way they have now done with Miyake. Despite past success, neither figure has the current appeal and lasting legacy of Miyake, and incidentally, neither was commemorated with a simple advertisement, garment, or red carpet look. Miyake’s acceptance in so many spheres, dance, academia, couture, art, etc., does not seem to have resulted in a greater depth of studying his impacts on each of these arenas. Instead, each of Miyake’s garments we are shown is meant to imply these varied worlds, his impact expressed through an inarticulate closet.

This is not to decry clothing as unexpressive. Some designers refuse the explanations and documentaries and interviews Miyake often gave, some even refuse to collaborate on museum retrospectives of their work. Miyake created avante-garde clothing that he sought to bring into the future through explanation. However, materialism, or rather consumerism, is not the same as someone being remembered through their art. So we must ask what it means that for many, Miyake will become equivalent to a turtleneck, his spirit frozen in the pleats. We must question if through, not a garment, but a garment projected on a screen or page, we look at the power of the garment or that of a product. Do we learn Miyake through his clothes, or do we simply see vapid pieces-of-cloth to be debated in price, clout and aesthetic? Is it enough to know that for every reposted garment there will be Miyake’s face? Can even this be guaranteed? Where is the humanity in an artist being remembered through an art that functions just as much as a commodified product?

Artists are remembered for their art. It would be unfair to claim this style of memorialization is specific to Miyake alone, yet perhaps his status as a clothing designer informs the way we choose to remember him. How is it that we can effortlessly switch between seeing clothing as pure art and pure product? When we look at a garment as one, do we consider that it is also the other? Because Miyake straddled these worlds so effortlessly, there is a danger in the two being conflated and confused. What is meaningful work is also pointedly tactile, and when viewed through the screen becomes just as much as a garment displayed for sale? In losing the specificity of how these garments are presented and discussed, the question of whether the memorializer intends to differentiate them is revealed. If an artist is remembered for their art and even that is not taken at its truest complexity, then we must question the motives of the memorial at all. Is it all for clout? Is it about the simple act of recognition, complexity or not? What do we require out of the interrogation of someone’s life and legacy, and is it the barest of minimums?

I am no expert on Issey Miyake, and I own none of his clothes nor perfumes(to my complete dismay. Then again, I wouldn’t wear all of his clothes. I wouldn’t wear every perfume nor do I connect with every Miyake-ism. But watching Issey Miyake Moves and seeing Miyake through the lens of someone who respected him, took him at face value, and illustrated so many aspects of what made his work so poignant, I couldn’t help but feel a stake in how his image has been flattened. I think of the thirty-page academic paper I read on the spirituality of pleats and the philosophy of A-Piece-of-Cloth, all the while watching Miyake repeat the necessity of research and functionality in his pleats. I think about when I tried on a pair of his pleated trousers for the first time this month, finding them perfect and sleek and brilliant. When I think of Miyake I think of his perfume that sits on my Grandfathers bathroom sink, once worn by my Grandmother, and sprayed often. I think of products, yes, but behind them are stories and emotions and power.

I write this piece as a student calling out to the teachers: Where is the memorial that Issey Miyake deserves?