If you allow it, a good fashion week can consume you totally. To love fashion and consume new shows is to devote yourself to three to six runways a day, to develop arthritic clicking fingers, and a sense of restraint. Still, when you find that first show that truly calls out to you, parting the clouds of irrelevance and repetition, it justifies the mad search. It is as if through chaos, you are seen.

The first show of Milan and Paris menswear to truly cut close to me was Jonathan Anderson’s JW Anderson SS25. The show’s first nine looks are broken up into sets of three: three military liner jackets turned bedsheets, high-necked leather vests that ballooned open at the hem, and bomber jackets in a deep set waffle knit. There were casual introductions to a new bag, a slouchy boot, and a culotte, but none of these garments was quite as loud as a scrunched sweater in an emerald leather patina stabbed with a suggestive silver “J” pin. Pants only appear in the show after the 12th look, and only 20 of his 56 models wear them. After all, why look to straight-leg leather pants or brown boots when the top is a crocheted jacket resembling an English homestead?

Vogue’s Luke Leitch described the show as “a disparate collage of adjacently sourced thoughts all set on designing garments that aggravated and stimulated the outer reaches of familiarity.“ Anderson, on the other hand, chose simply to call it “Irrational Clothing.” I interpreted irrationality as a lack of styled “characters” with focus instead placed on the versatility and malleability of strange and evocative garments. Anderson’s work is as popular as it is partly thanks to his media savvy, but also for his ability to root both Loewe and JW in a sense of thoughtful appreciation and consideration of craft. While much of menswear is devoted to the construction of different platonic ideals for basic garments, Anderson’s role in creating crafted fashion items is to argue for new shapes, directions, and silhouettes. The show balances between the oddity and specificity of these pieces, and a normcore sensibility in which looks are perilously close to looking easy to wear.

Anderson’s last look cements the show as journey from garments broken down, scary, “fashion“, and niche, into fully styled, normal looks. A military jacket has tidy, almost pleated shoulder flaps, baggy jeans come with a belt at the ankle but above the hem, and boots sweep up the shins with the option to tuck in pants. There is a binary explored in this difference as well, of garment as gender confirming/conforming, and as gender bending/confusing. This final look can be seen as one side of that binary compared to the early concept looks, or an evolution into a formulated character straddling that binary.

The fashion industry is strange about menswear. Menswear shows happen right before couture as if to signify a grand split between art and finance, innovation and appendage. This is the shadow that hangs over menswear, at least until the streetwear boom in the 2010s revealed the artistry in streetwear, a longtime racialized and gendered sect of fashion not taken seriously in critical spaces. This helped shift these designers into the mainstream, taking with them favorites of the menswear archive like Rick Owens, Hedi Slimane, and Raf Simons, giving each new lives in modern menswear fanatics. The streetwear boom ended, but menswear obsession didn’t.

There is money in the nicheness of menswear, but this confuses an industry that has for years pigeonholed and scoffed at the category. To take one menswear niche: a traditional, ubiquitous, trendless, easy elegance one could look to this season’s Auralee, Armani, Fendi, Fear of God, Lemaire, Our Legacy, or The Row and find totally unique iterations of a traditional men’s dress code. There is a difference of course, between a brand like Auralee or The Row, which have boutique views of men’s traditionalism and minimalism, and Fendi, which latches on to the convenient cultural obsession with this aesthetic for an easy sale. To the larger players, nicheness is something to invest in fickly. Most of the larger brands have menswear as a less profitable but shiny appendage to their business and use general and inoffensive masculine codes as branding exercises - as a flexing of influence and breadth.

Anderson’s show is a fantastic example of how modern designers are approaching the menswear market. There is a pragmatism in designing without as many barriers between who can wear what - garments include gendered signifiers without being limited to wear. Gucci replicated womenswear looks for its men, Pharell’s Louis Vuitton dresses women in “ menswear“, and Anderson’s show which claims to include two separate shows in one presentation completely blurs the line between specialty designer products for men or women. Any gender can buy into Vuitton leather pants styled by Anok Yai, just as one of Anderson’s bombers could serve as a dress or match a pair of pants.

But Anderson’s show was just the beginning in a multi-week trend of eschewing menswear altogether.

Other runway shows that combined men’s and women’s shows like Anderson included Lemaire (separate CDs for Men’s and Women’s yet unified concepts and garments), Kenzo (the starkest of gender splits), and Wales Bonner. I thought it potentially significant that Dries Van Noten’s final runway show after nearly four decades was a men’s show - rarely the site of momentous fashion finales. Still, as Dries said at his show, “It’s all one big happy world, and everybody can wear whatever they want.” Undercover’s Jun Takahashi was more specific in this regard, saying “He wanted to provide a men’s collection which also has elements that are feminine,” reported Takahashi’s translator: “because he thinks this border is getting less and less.”

For collections buoyed by fanatics of a long gendered archive (adherents of Undercover and Dries but also Comme des Garcons, Junya Watanabe, and Margiela) many have taken to mixing the codes of long-lost and loved menswear and womenswear collections together, reminding fans of old days and opening up garments to those previously unable to buy or wear them.

Rick Owens is certainly a designer whose collections and collectors are strictly gendered (ask a man in geodunks how many silk lilies slips he owns & a queer in Owens rags how many Champion pentagram drop shorts they own). In his men’s SS25 show entitled HOLLYWOOD, Owens moved from the personal space of the apartment he hosted shows last year to the format of a grand parade of fashion students and diverse models - gender, age, and look were with as little formalization as possible. Each look was replicated dozens of times over by this diverse parade, culminating in a metal structure decorated with models and flag bearers. Owens described the show as an “exercise in thinking about body types. Because I’m thinking we have 10 looks that have to accommodate every single body. So how do we do that? How do we make it convincingly look like Rick Owens looks?”

Rick Owens is marked by the “cult” of his fandom, the futurism of his fantasy, and the extremity of the subculture he unearths to the mainstream. Because of this, he has incredible opportunities to set the standards of gendered aesthetics and performance in his world or to eschew them entirely.

The greatest development in Owens’ work over the years is the shift from archetypes and characters being welcomed into the fold of his world (a Dietrich femme fatale, a crust punk, an Eastern Orthodox monk, a step dancer, etc.) to the formalization of more complex Owens types, silhouettes, and characters. They become defined and understood almost solely through Owens’ uniform and fantasy. In HOLLYWOOD though, Owens imagines the most pared down and ubiquitous fantasy of masculine dress he can - a more generalized look beyond Anderson’s focus on the garment and its minute gendered potential. The garments have histories and contexts, but the design of each is to bring any person regardless of body or gender into the fold of his uniform. The more abstracted the role, the easier to dress in Owens without a gendered association attached (starlet, monk, etc.). The fact that the garments are coded as masculine is incidental.

Owens reminds us that clothing is important in fashion fantasy, but those who wear it are just as important. The power of opening up fantasy so broadly in a show of such few yet versatile looks is that it can become so easily refashioned by an eager audience. Menswear becomes a style, not a rule of dress.

After the weeks settle down and the shows simmer into memory, a few always stand out. These are the special runways, those that refuse to disappear behind chaos and call out for new desires and garments and looks. This season the show that has lingered was once again, Martine Rose.

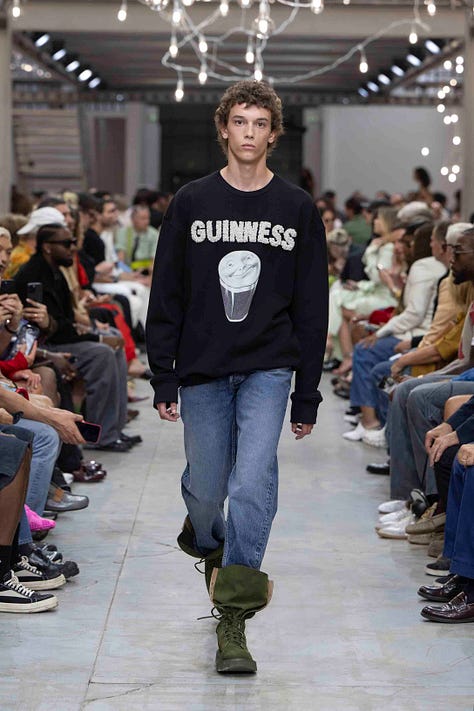

I wrote recently about Martine Rose and constructing gendered uniforms - she is a master of deconstructing gendered dress in a way that is playfully natural and incorporates subculture’s role in upholding/breaking these binaries. In her SS25 Milan show, she focussed on the term “Messiness“ (not dissimilar to Anderson’s “irrational“) and used bulbous prosthetic noses as a means of interrupting an audience’s ability to see the models as characters. False faces redirect attention from the fantasy of a model to tactile garments. The clothes were excellent - a refined and heightened iteration of Rose’s classic codes (the cropped hoodie, crotchless pants, jerseys, distressed leather) and explorations of how to normalize “feminine“ garments as ubiquitous. Leather shorts become a knee-length skirt, shirts are given scrunchy forms and sexy closures, socks turn into sheer stockings, and handbags abound.

If there is a distance or barrier to Rose’s fantasy, it is in allowing the self to look and feel ostentatious. Her clothes have the benefit of feeling like vintage, and Tamara Rothstein’s styling for Rose has a fantastic naturalism. Her focus is on the garment like Anderson, but the garment’s concept never has the opportunity to define the outfit/wearer. Her sense of fantasy building, of a subaltern queer analog Britain, is as strong as Rick Owens’, but replicable by the average person (try authentically recreating a HOLLYWOOD look for under $500). This is the power of Martine Rose: a garment-centered, achievable fantasy of utopian gender-fuck, class upheaval, and pure human joy.

Consider Rose’s final look: fishnet socks and strappy bulb-toe loafers meet the end of a model’s flowing extensions. Tiny belted short shorts and a sport blue tank top that says “Martine”, the neckline a deep feminine square falling deep down the model’s muscular chest. Behind a gray hat and a yellow nose, the model’s face is indecipherable: all you can see is their pursed lips.

It is a summer night, a day at the game, a morning after, or a jog all at their sexiest most perfect form. It refuses normalcy yet feels accessible. It is the moment fashion becomes real, becomes yours and mine.

It is why I watch.