Before New York Fashion Week started it was being divided. One tweet suggested there was first the Fashion Week of the CFDA with a roster of new talent and award nominees battling for eyes and time. Then there was the NYFW of tradition, flush with cash, organized into tidy processions of algorithmic celebrity guests and strung together by words like “market”, “timeless”, and “Florida”. In disagreement and battle, they met.

This was the second fashion week I’ve been in New York and called it home, the fashion week with designers literally around the corner, the fashion week I actually work. This was the fashion week I attended my first show, the week I passed editors and writers whose work taught me to love fashion. This was the week I drove across the Brooklyn Bridge for the first time in a white pickup truck while Pavement played on a tinny iPhone in the glove compartment - a million events forming an emotional mush of cliche.

But this is a moment to fully unpack on another day.

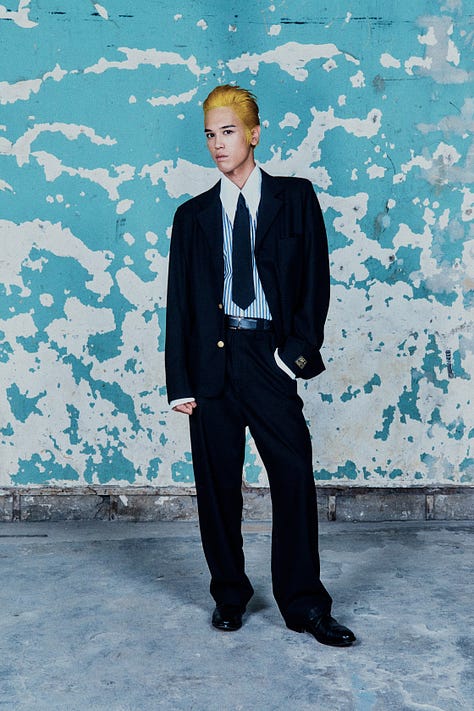

The first moments of New York Fashion Week that touched me were feelings of old friends returning, growing, expanding. Willy Chavarria put on one of his best runway presentations, providing a broad range of settings and wearers for his voluminous proportions and Chicano touchstones. Usually, Chavarria’s runways offer the grandeur of billowing pants and lapels, hats, roses, velvet, draping, and extravagance. For SS25 he embraced the uniform ubiquity of a Lemaire or Our Legacy; still rooted in culture, time, and place, yet styled for comfort and diverse bodies and occasions. It’s a hell of a uniform.

Chavarria’s looks blended denim and khaki, brass-buttoned blazers, and dangling keys. He imagined the chic of working-class farm workers, the details that could heighten and formalize the banal. His luxury expands generously between Paloma Elsesser’s pristine white tank top and the frilled neck of a sheer gown (my kind of wedding wear). It had the politics of an ACLU tee and a Wall Street setting (the show was titled América) along with the united appeal of an already partially sold-out Adidas collection with pointed toe sneakers and high shouldered jerseys.

Something was welcoming, almost intimate about elevating the regular, showing that chinos and a plaid button down can hold luxuries, erotic expanses, and means of identification. I understand the necessity of spectacle, of intricate made to order suits with roses and floor dragging cloth, but none of Chavarria’s work has done more for me than his simplest, his easiest, his tackling of the most expansive: América.

I guess it was American. The American flag hung over the runway, always the least useful and most overused tactic in examining patriotism and national identity. Diaspora, American subculture, and American space are important to Chavarria’s work, but the flag fell flat, perhaps just to me. Chavarria’s work is American without a flag or a title.

Also expanding their uniform was Who Decides War, receiving press for Air Jordan & Pelle Pelle collabs and a roster of rappers in attendance. Who Decides War invokes the luxury streetwear market boom of the 2010s with its church window motif cargo pockets, heavy embroidery, and distressed patchwork denim. While most work seems primed for ready-to-wear shelves, this season took on increasingly detailed degrees of distressing and draping. Ghostly dresses of ripped cloth met skirts resembling Grecian robes, and tight jackets of cinched belts juxtaposed the swinging military straps that careened off thick nylon coats. Everything felt custom and impossibly minute, like the columns of a decrepit castle or the folds of a Pelle Pelle leather

This season was titled “ascension“, and one could sense the house was both rising in quality and diversifying its clientele. They also dipped into the aesthetics of tried and true New York indie mainstays that would make Who Decides War more natural partners on the rack beside an Eckhaus Latta or Collina Strada. Their ascension is a welcome one.

Speaking of, Eckhaus Latta was one of the few to openly admit and advertise seeking a basics program. Art is fun and all, but the money being tossed around on shows like Toteme or Khaite must also be hard to resist. The Eckhaus Latta show included Ella Emhoff, Moses Sumney, and Julio Torres, which is to say it is no longer quite so indie and niche. The brand’s offerings were decidedly muted, if not outright commercial, with denim washes toned down and colors dialed back. Eckhaus Latta’s “simple“ clothes are still gorgeous, and often the kind of aspirational basics for a clan of coastal gays and theys. Still, it is their oddball washes, funky materials, and rich palettes that keep me a fan.

Another note about Eckhaus Latta: the show took the form of a dinner in a Tribeca loft with guests dressed in the new season, who then informally walked between the tables. Laia Garcia-Furtado for Vogue mentioned the affair felt like a wedding. A separate lookbook was released in tandem with the show with twisted models and silhouettes of the new shapes.

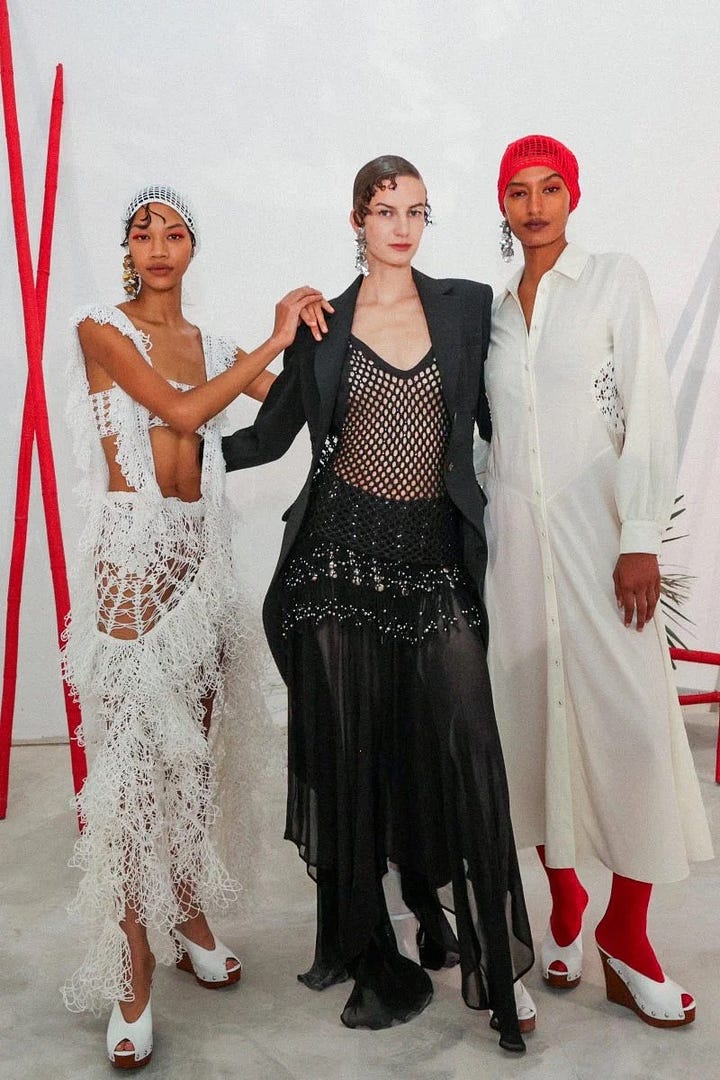

This was a season in which many opted out of traditional runways in favor of intimate “experiences“. Diotima had models move in processions, then posing in groups by floor-length windows and red candlelight. A shame these looks couldn’t have been better documented in the matching lookbook, for they were exceptionally styled: taking Diotima’s simple knits and constructing them in just the right bone shade beside just the right red stocking, matching beaded fringe with heeled clogs. If Diotima’s weblike crochets weren’t enough, garments this season also featured skirts and dresses lined with flowers, fringe that drooped lower, and hems that scraped lower and lower still.

The craft and time involved in constructing Diotima’s garments is what makes them seem so personal, so tactile, so warm. This collection’s greatest strength was highlighting that sense through an equally warm and personal environment.

Even smaller than Eckhaus’ Tribeca loft was Zoe Gustavia Anna Whalen’s fifty seat dinner show in a Tribeca gallery. Lace tied lookbooks showed moody upstate New York sunsets, a farm house, and sensational dresses.

Garments were treated with paper mache or constructed of napkins. Boning in dresses and corsets twisted and dipped like bleached bones of aquatic animals. Pieces opened, sometimes invitingly, sometimes inadvertently, sometimes by design. The clothes labors of love, of time’s passing and response through repair and refashioning. They are sexy yet frayed. They looked at home in the coziness of the woods, they looked at home at her dinner of friends and collaborators sitting on pillows on the floor.

Confession time: I worked both the Diotima and Zoe Gustavia Anna Whalen shows as a Production Assistant. At the latter, I helped to serve and partially prep dinner. Witnessing a fashion show is very different from examining a lookbook. Physicality brings with it new standards and blinders. At the ZGAW show, I experienced a community that felt familiar, Queer, cozy, and inspiring, all inexplicably within fashion.

I’ll reiterate: this was a moment to unpack for another day. In reference to her show though, it goes beyond a moment to intellectually process. The dinner was a more personal window into the kind of fashion space I wanted, maybe needed. I am still verklempt.

Still, many indie designers opted for the bright lights of the runway. Grace Ling matched slinky and silky shirts and slips with coats and tops that resembled singed paper. Models were wrapped in complex silvery formations, a breastplate, a bird fluttering to a branch, a webbed hand on a thigh. While many of these experiments in texture were welcome, it was hard to imagine the garments anywhere but a smoky runway or a custom order.

Women’s History Museum was also fascinating, set in a church decorated with broken glass; a high-definition reproduction of Mcqueen. The clothes had a similar affect, with animal footwear, jagged houndstooth sets, skin, trash, and sheerness. Highlights included penny chainmail and enticingly weird jackets. I was less partial to the block letter slogans, a genre of trash that felt out of place, if not generally overdone.

The show was certainly shakier than early Mcqueen, but I couldn’t say that much else in the city looks like it. Many attempt to copy the spirit of McQueen but few attempt to match his spirit with the technical skill he had. There is thinking to create a dress from plastic, and there is being able to cut it just right.

Another technical newcomer to the runway circuit was last year’s CFDA fashion fund winner Melitta Baumeister. Baumeister usually releases collections through fun virtual lookbooks. Colors pop and the scene is always bare yet bizarre; a suitable landscape for her bulbous and oversized proportions. Sometimes models are joined by piles of snakes, ellipticals, or fruit.

Baumeister’s stiff pleats and exaggerated proportions make them ripe for experiments in movement - SS25 began with Paralympic gold medal track and field winner Scout Bassett. Basset signaled sport, the show’s theme, and what better way to explore movement. Jerseys came in a monochrome synthetic stiffness, signature sharply curved tops met biking shorts, and one giant sweatsuit seemed dyed by a yellowish sweat. Elsewhere, it was refreshing to see pastels both in solids and in pale springtime combos cover Baumeister’s dresses.

For a designer who usually displays their work in vacuums, it would have been interesting to see her work in a different space. This doesn’t mean a garment should match its runway setting exactly (looking at you Alaia) but that an opportunity for a conversation between the two was lost. These are powerful and dramatic clothes that change and create space. Just as we should see them move, we should also see the places they can live.

Luar wasn’t the last show of the week, but it might as well have been. Lopez is a master of fashion spectacle, an older, distinguished seeming runway of capital S Supermodels, Sex, and Stamina. This is a nostalgia powered by designs that feel strikingly modern, sorely missing from racks and editorials, and it is this impact that drives the final capital S to Lopez: Stars.

This year it was Madonna and Ice Spice outside Rockefeller Center in a sea of reflective black uniformity and splitting bass. Lopez sells his clothing at few retailers yet consistently shows over fifty looks. Each is beyond necessary. The rhinestones on mosquito net tracksuits glittered under the spotlight, flashes of knees poked out of the slashes in voluminous suit sets, unzipped cummerbunds extended up the chest on another black jacket, and caramel croc boots replete with straps met a high shouldered jumpsuit with fringe at the neck. Sometimes all that was necessary was leggings, briefcase, thick shades, and a crewneck reading “Luarsexual“ in cursive, black on black.

The attitude here reminds me of Martine Rose in Lopez’s rootedness in the ironic normal, the subcultural uniform made mass, and the pragmatic. Each of his garments is excessive, luxurious, and precious as a means of enhancing the already pragmatic. A sleek gray trouser is still a trouser, this one just has a small train. They are defined by a fabulousness you could live in - what a concept for fashion.

Each season I think the same thing: I hope this is the season Luar ready to wear is made more available. I want to touch every one of these garments, to run in them, to dance, to zip them, to show too much skin. I want to live in Luar. Call me a Luarsexual.