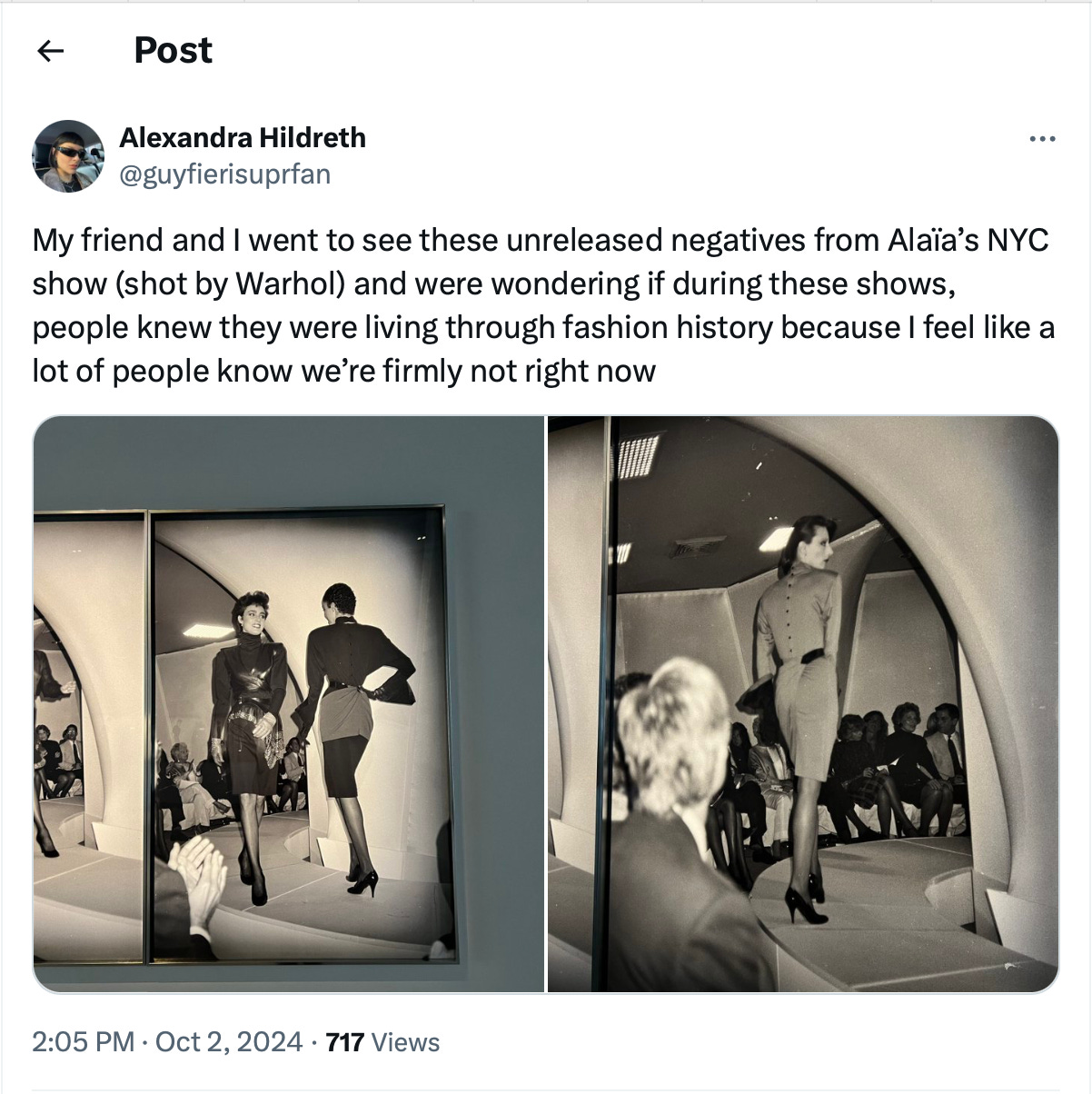

Synthesizing Paris Fashion Week was exhausting and I wasn’t even there. Beyond the endless shows, events, announcements, guests, and details, I turn to a question Alexandra Hildreth posed last week:

In a landscape with dozens of fashion shows released each day almost simultaneously, what do we devote attention to? What do we study, what do we remember, what sticks?

Daniel Rosebury was certainly designing with history in mind for his Schiaparelli, titling this season “Future Vintage". Schiaparelli offers more than everyday fashion irony and spectacle, it has a legacy of classy subversion, an insider’s touch. This season there were corsets and jeans and simple suit sets to match toe-studded slides. Light wash denim, tan denim, denim trench coats, denim dresses, and more. Things got fussier with zebra print sets and billowing beauty linen numbers. You could almost see it as heightened everyday clothing, not necessarily the niche Schiaparelli is known for.

What does Rosebury mean by “future vintage“? Is denim chosen because it ages well, or because of how much vintage denim exists? Are the cuts of dresses “timeless“, or were they based on archival Schiaparelli models? Is “future vintage” a statement of quality or aesthetic? Moreover, to designate this specific collection as “future vintage“ implies the other collections are not. What luxury clothing is not imbued with the fantasy that heightened quality and timeless status symbology will turn a five-thousand-dollar bag into an heirloom?

Rosebury shows us how shallow this kind of virtue signaling can be for such a wasteful industry while also showing the importance of historicity in selling clothes. The growth of archive fashion online has heightened this consciousness. A reference to an “archive“ piece gives the new garment intellectual cache, a synthesized past, and a bet on something already proven to sell. Stories sell.

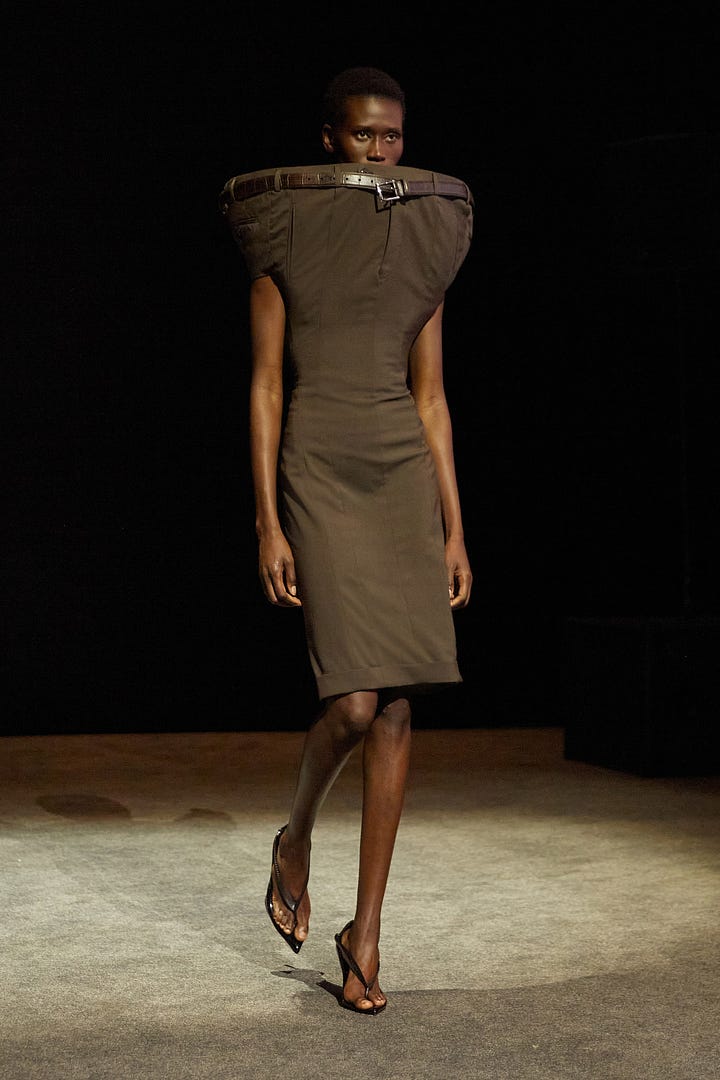

Take, for example, Martin Margiela’s jacket of stitched-together belts, or Junya Watanabe’s blouses of old zippers. Hodakova has been making bags, dresses, shirts, anything really, using similar looking stitched-together belts. This season also happened to incorporate a show stopping dress of golden zippers. The references were mentioned by others, but the difference with Hodakova is more than craft and exclusivity, it’s sustainability.

Hodakova constructs all of its garments with deadstock fabric and upcycled vintage, meaning the clothes contain historicity & are sustainable by design. Rather than seeing “archive” deconstruction as merely a product to mimic, Hodakova treats these references as effective techniques for crafting more ethical clothing. As winners of the latest LVMH prize, their show represented optimism about fashion’s adaptability.

The show itself was effectively split. First, there was the wonky and deconstructed; think the belt and zipper and boot and button and ruffle dresses and tops expanding and leveling off smooth at the shoulders. A classical pastoral landscape on bags and jackets becomes a dress, its accompanying picture frame dangling at the ankles as if the model were springing through it. Then there were basics like belted camel jackets, wool zip-ups, long shorts, and preppy layered sweaters over jackets. Both styles came with a sharpness, a lack of agedness traditionally associated with “upcycling“. If Hodakova were simply this it would be pushing the needle. It is so much more.

On the club kid side of the Paris avant, Benjamin Barron and Bror August Vestbø’s All In went for more visible seams. Titled Uptown Girl, SS25 embodied what Barron and Vestbø describe as both “an attempt in everyday life.” and “trying to impersonate someone of a different background“ (here, 1988’s Working Girl was a prime inspiration). Like Hodakova and others, All In takes a collagelike approach to creating clothing traditionally seen as sleek, simple, and expensive. They might be seen as a result of a trickle-down of this aesthetic if it wasn’t styled so well, and if the garments weren’t so pervasive.

This season, the draped presentation of a garment hanging off the body is key, along with plenty of skin and sex. A Guess Jeans collab allowed for lots of Frankensteined denim, sometimes as severe as a denim waistband holding poofs of tulle and lace. Layering is odder here, as if the models cut up their work clothes for a rave as if they were stuck together in a tangle. It’s a victorious chaos. Even if it’s mainly sustainable in aesthetics, All In shows are unmistakably sexy.

Beyond the regular questions of fashion capitalism, taste, history, and artistry that Hildreth mentions, this fashion week had other specters of anxiety around. I’ve been thinking about the future these days. Bombs hurrying climate change, “doomsday“ glaciers melting faster, hurricanes and chemical plant meltdowns showing us a future of overlapping catastrophe. The escalation of climate change in the past month has served as a reminder that our lives, societies, and priorities are teetering upon massive change, if not eventual collapse.

As someone who writes, who loves art, who makes art, I have been considering what art can do in catastrophe. More so, what can a medium like fashion, one of the world’s most wasteful and fickle, do to make a difference in people’s lives. If we are not living in a period of “historical fashion“, what are the shows that make fashion mean more than pure consumption or posturing?

I’ll admit, my first thought wouldn’t have been Comme Des Garcons. There are now numerous sublabels and designers under the umbrella label, each creating different amalgamations of art, fashion, and utility. Comme Des Garcons mainline is the artsiest, the most sculptural, and operates under the highest concept. These are museum pieces, not necessarily for a hike or work commute.

This season was different. Dresses were composed of geometric mesh, that held crumpled fabric, deflated floral structures, plastic, feathers, maybe trash. Some dresses are white puffs, others pleated obelisks with jagged hats. Sleeves of red tulle droop low beside crimson patterned structures. Dresses look like pillows with yonic slits down the middle held by ribbons and bows holding models in the center. Some looks resemble cat trees, dildos, columns, pillows, Marie Antoinette, trash. It is one of her most compelling runways of recent.

Kawakubo proclaims, “With the state of the world as it is, the future as uncertain as it is, if you put air and transparency into the mix of things, there could be the possibility of hope.” I think of air when I watch the videos of the show of simple slow pacing models click clacking in white boots without a soundtrack. The dresses bounce, silk and ribbons sway. I think of transparency, the truth of garbage behind avant, the protective nature of geometry, couture as floatation device, fashion aesthetically zombified.

Kawakubo portrays an artistry of collected trash used to reconstruct memories of complex human civilization. Queens of trash, pet toys of trash, beds of trash, sex of trash, Roman ephemera of trash. Kawakubo claims here to be moving on from anger, but even so the empress’s clothes are trash, civilization trash. On an optimistic note, all trash gets to be art.

High concept art is often seen as a balm to chaos and authoritarianism, a celebration of the soul, the superfluous, the intellectual, the fringes of what we have made. High concept fashion is usually scorned for these same qualities, mainly because of their far more visible price tag. There are few examples of runway shows with primarily unwearable clothes that make historical, political, and social impact because of this barrier. This was an example of extremity and chaos as an effective and compelling politics, and aesthetic. Here was a thoroughly modern, immediate, political deconstruction.

Kawakubo isn’t the only designer peddling deconstruction, though she’s one of the few crafting compelling politics along with a sellable product. Ann Demeulemeester, now under creative direction by Stefano Gallici, presented a case for a trendy deconstruction. For SS25, Gallici blended the strappiness, gothic twists, and tailoring of original Demeulemeester with a “coquette“ lightness. There were pastels and ribbons, short skirts and ballet flat lacing. It was clean, styled well, and commercial. It was a platonic ideal of sorts: a respectful conjoining of past and present under easy commerciality.

This is not everyone’s preferred path for Demeulemeester. Fashion critic Odunayo Ojo tweeted the following:

When are rags positive, edgy, interesting? When are rags rip offs? Does “refined“ mean uncommercial, original, art? Ojo raises a simple distinction between the Ann Demeulemeester brand, and designer, and the latter is long retired. Demeulemeester the brand becomes a site of experimentation with a new marketable deconstruction. It is not the continuation of the founder’s work, but a repackaging of their most sellable codes.

It’s one thing for a centuries old family maison to do this, or even a decades old legacy house. It’s another when the designer is still alive. If Ann Demeulemeester is not Ann Demeulemeester, just a trendy holographic reproduction, what is its edge? Can it be compelling? Will it ever be anything more than its foundation?

I was asking the last question a lot, especially during the first Dries Van Noten show without Van Noten as creative director. Like Demeulemeester, the looks were sharp and the garments pretty if not trendy, but all I saw were the dollar signs behind a clear push towards handbags and ballet laced shoes. It’s not that Van Noten’s team isn’t capable, but I wonder about the raison d’etre of the clothes, or even the house. It could be to keep jobs or to return an investment, but do we really need a faux Dries to pump out imitations and investor-safe newness for quality? Do people want to buy Dries Van Noten that is not Dries Van Noten? Do people want to buy Ann Demeulemeester that is not Ann Demeulemeester? Do we need new clothes that much?

This resurrected third of the Antwerp Six is small potatoes compared to the machinations of LVMH and Kering. They gave Saint Laurent boatloads of cash for a Bella Hadid comeback and a double show. It was better edited than many of Anthony Vaccarello’s shows, and far more wearable. Like Vaccarello’s recent menswear, this season highlighted tailoring that resembled the uniform of Yves himself, along with an homage to the oft rejected 1980s period of YSL’s bold colors, crushed velvets, and complex embroidery. Even with this ugly-chic swing, the show was essentially a display of basics - a competitor for The Row or Bottega’s effortless chic. Was the money worth it?

This season also justified my belief that the simultaneous relaunches of Chloe and Alexander Mcqueen are presenting near identical kinds of work with diametrically opposed results. Chloe is the golden child, this season with a gorgeous color palette, bags with charms, and distressed leather. Mcqueen is the problem child, juggling uninspired tailoring and oddball sheerness with the occasional avant beauty. Both are latched on to 90s/00s archive fever, constructing complex campaigns of celebrity dressing and editorials to inflate their flailing brands with cache. They both feel fleeting.

Work like this attempts to distract from doom. These pieces/shows/boardrooms want you to spend the same, live the same, think the same. Their sense of newness is repackaged nostalgia and that is all it can be. As nice as looks from these shows are, as compelling as their styling may be, they don’t carry any sense of real life immediacy. Their datedness is dangerous.

By all accounts, the first Valentino runway from new creative director Alessandro Michele should be exactly as dated, exactly as dangerous. I hold this show to an especially critical standard, both because of the money and prestige behind it. Still, trendiness will always be less sustainable than timelessness, and Michele’s iteration seemed more intent on selling a compelling vision of storied, antique luxury than reinventing the wheel.

Michele’s raison d’etre for Valentino was craft, sumptuousness, and an old world inflected luxury that is timeless but flamboyant. Everything was tidily cross referenced to the Valentino archive, yet was styled in Michele’s ever popular eccentric signature. His work speaks to more than the aesthetics of older luxury, he reclaims its function as elegant, longlasting, timeless. Where Schiaparelli needed to invoke “future vintage“ and heirloom, where a Demeulemeester or Mcqueen needed an archive citation to make trendy, fickle clothing, Michele’s work feels effortlessly storied.

Michele’s luxury is pragmatic. It offers risque oddity through runway spectacles yet produces work that feels unapologetically bold. Under Gucci his work was often logocentric, yet balanced with a modern mentality of collaboration and sumptuousness. Michele’s Valentino is all sumptuousness - not a “V“ in sight. Instead there are black frilly dresses speckled with sheerness, blooming scarlet hats, the deep fuzz of fur and drooping cardigan, embroidery, gemstones, wide lapels. One can imagine all of these things as being luxurious forever.

85 looks is still extreme, and Michele is still rejoining a fashion machine. Still, he melted my cynicism with a serious romanticism.

This was my first season attempting timely fashion week roundups. This meant quicker reviews and turnarounds, less thought, a faster pace. Sacrifice.

Reaching the end of that experiment, I discovered there was still room for a runway punctum - a fashion that touches beyond what words can contain. It’s an easy out at times, but is also an affect worth respecting. The ability of clothing to touch us, literally and metaphorically, is what makes it a unique medium.

I will attempt to fight through all that was indescribably potent about Jun Takahashi’s Undercover SS25. In a literal sense, the show was made up of a tailored bondage uniform in an array of washed out salmons, navys, and eggshells. The ensembles were dripping with straps and buckles, punk baubles on shoes and collars, spaced out ugly florals and straight laced checkers. It was all cut with such incredible precision, such love, and for a very specific kind of powerfully edgy ease. Takahashi says of the show “adding some fetishness and being able to adjust the size and the silhouette can make daily clothes sexier and also more elegant.”

This was the first of Takahashi’s womenswear shows in a while to not come with a live runway. Takahashi is consolidating to one live show a season. He recently mentioned his dismay at fewer guests asking about or paying attention to his clothing at fashion shows. Perhaps this is why he consolidates, why he set up his show like an art installation with an accompanying lookbook. Perhaps Takahashi sees an art form in death throes, so self obsessed it can’t imagine that it will drown, so tied into capital that it has lost its purpose. Perhaps this is why Takahashi ends his show with saints crowned in gold auras, struck by arrows, bound in zippers and belts.

Whether he did it intentionally or not, Takahashi’s fashion saints, his angels of death reflect a quiet melancholy at an inflexible industry. They are icons of fashion past, bound to glamour, trapped and painted, posed as eternally shot. It’s a fantasy of death made into sex, corpse made into memory.

If fashion is to die, let it be commemorated as elegant spirit. Let it be a binding uniform of sainthood. This is a luxury that will fall with grace.