Hello readers! Oh how time flies… what a month. If you’ve heard from me less it’s because I was putting the finishing touches on a NEW ZINE!!

JUNYA WATANABE’S DISAPPEARING SAPEUR comes in a limited run of 50 with glorious bleeding color, and a full piece on Junya Watanabe’s appropriation of the Sapeur movement. The zine was conceptualized, created, and distributed with the help of Nan Collymore, an incredible artist whose work you can discover here. This is my first foray into professional print, and I’m very pleased to say that the zine is currently available at New York City’s iconic Casa Magazines.

Zines are available for $15 at Casa, or I will deliver one to you. Direct all inquiries to my email at Bburton206@gmail.com

I’ve included the first part of the zine as a sneak preview for you, my dear reader. Enjoy!

“the risk of visibility is then the risk of any translation. . . . The payoff of translation (and visibility) is more people will begin to speak your tongue.”

- Peggy Phelan, Unmarked: The Politics of Performance

In July 2024, Junya Watanabe showed his spring-summer 2025 menswear runway collection, a flurry of denim tuxedos, patches, wingtip Trickers, pocket round glasses, and droopy bow ties. Near the end, jackets were shed to reveal tight white shirts, patchwork rock t-shirts, lone silks at the neck, and loose totes. When Watanabe discussed the show he centered on denim as “theme” and “challenge.” For many though, the detail that revealed the collection was the red carpets the models strode down.

To any disciple of Watanabe’s menswear, the bright red carpet instantly evokes FW15 menswear. In that show, there were as many skinny suits as there were tuxedos and bow ties, but double the top and bowler hats. There was patchwork, but monochrome - there was only one white jacket, all else was blue, black, and grey and all the glasses were round.

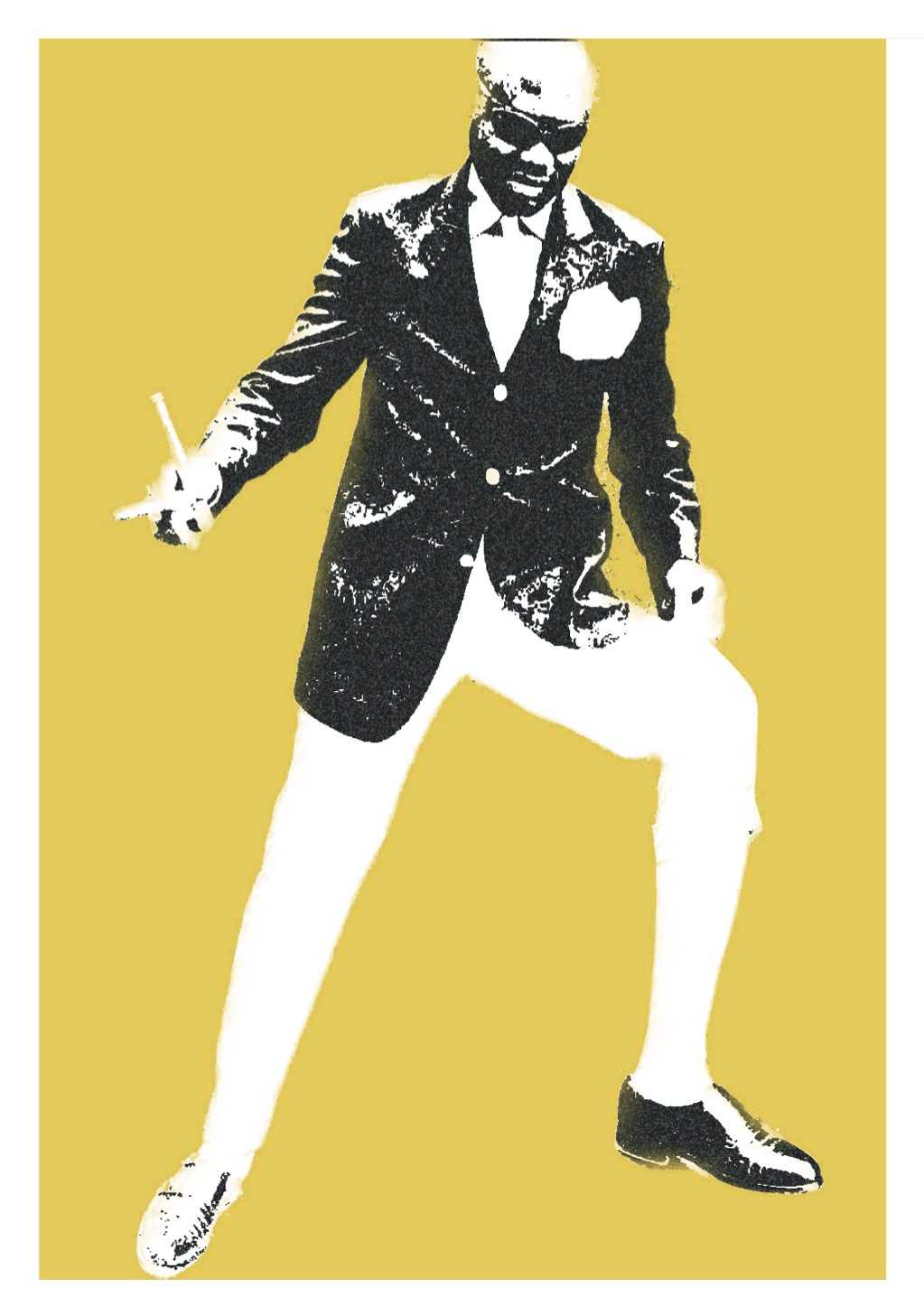

Another difference is the models, almost all of whom are Black and members of La Sape, a Congolese subculture centering style, performance, and designer label. These disciples, Sapeurs, who have themselves been longtime supporters of Watanabe’s conservative dandyism are the focus for this show. Watanabe’s Sapeurs are more than models, they perform. Suzie Lau framed the show as a redefining of power and control, writing “The focus was on the people inhabiting the clothes – they were in full command of their attire as opposed to the other way around.” FW15 is remembered for serving as a true blank canvas for Parisian Sapeurs to illuminate. It was an unusual ceding of space and power. Fitting then, that when Luke Leitch refers to the iconic show in his SS25 review, he calls it “his [Watanabe’s] Sapeurs show.”

Imagining this scene, this dynamic, one may wonder where in Watanabe’s SS25 tribute to FW15, are the Sapeurs. While in FW15 non-Black models resembled ”dandified Edwardian hoods,” “undertakers,” and “Abraham Lincoln,” SS25 was far more diverse and diffuse in casting, meaning, and message. Does this mean material (denim) comes before subculture? Even without blatant acknowledgement the Sapeur’s spectre remains - SS25 is a tribute to a tribute. What to do with these spectres, their style, their dance, their recontextualizing of Watanabe? Why do they disappear?

Watanabe’s turn here raises the suspicion: Is there any place for subculture in our globalized, corporatized, sanitized landscape of fashion?

Origins of Le Sape

Historians and critics disagree about the origin of Le Sape, but chart a throughline of vestimentary culture and dandified dress that began with the initial contact between Africans and Europeans. It wasn’t until the 1960s that the term Sapeur came into use as a way of describing a more unified subculture of men defined by music, subversive politics, and predominantly, strictly fine dress. Sape/Sapeur refer to the French word for clothes, while also standing for “La societe, des ambianceurs et des personnes élegantes.” The Sapeur’s dedication to style is almost religious, and within the subculture that religion is named Kitendi. Didier Gondola defines the Kikongo word as “more than just cloth it represents a cult of cloth, a sublimation of the body that has been regenerated by cloth.” The Sapeur does not settle for just any cloth. He prefers the sapeurs from Kinshasa are extravagant, even eccentric while those from Brazzaville are more sober and classical griffe: a luxury designer garment, the more expensive, limited, and runway, the better. The particulars of labels are essential to the uniformity, stability, and personhood of Le Sape.

Sapeur obsession with luxury fashion coupled with the very real threats of poverty, instability, and violence propelled many to immigrate to Europe (particularly Brussels and Paris). In interviewing Sapeurs preparing to travel to Europe, Gondola records many responding in Lingala: "na ye ko meka nzoto." Gondola writes that this can be translated as ”I came to try my body." and that “the sape envelops a metaphorical body. It dresses the social metaphor which is the body.” Other Sapeurs call Europe a “mecca”, a “paradise”, an “invisible nation”

Diaspora fractures Le Sape’s meaning. In the most local of terms, “sapeurs from Kinshasa are extravagant, even eccentric while those from Brazzaville are more sober and classical.” Some Sapeurs, with the memory of dictatorship in close memory decry violence, crime, and politics in favor of gentlemanly good manners. Belgian and French Sapeurs, sometimes squatting, living in the country illegally, or supporting family back home will turn to crime or con. All the while, affording such expensive griffes often requires its own loopholes.

In 1999 Michaela Wrong interviewed a Sapeur named Colonel Jagger who claimed “If anything Sape has become part of the mainstream. It's been vulgarized. Government ministers wear couture and have Sapeur hairstyles. Just look at the Church pastors- even they now assert themselves”. In 2025 the Sapeur has been commodified, referenced, and integrated into a niche sect of pop culture numerous times. Sapeurs appear in music videos for SZA and Solange, they star in Budweiser commercials, high-profile European photographers seek them out to document them, and countless archive fashion accounts on social media repost their pictures. As well as Watanabe, Paul Smith designed an entire collection dedicated to Sapeurs.

Monica L Miller writes in her history and analysis of Black Dandyism that “dandyism’s current close ties to global capitalism may signal the death of or certainly a significant change in its ideological force (Roland Barthes’s axiom “Fashion killed dandyism” echoes here.)” Le Sape refashions and intimately styles brand names, but Le Sape is defined by the ability to refashion and combine them. How do those styles, the brands, and more generally, that sense of distinctiveness shift when Le Sape is globalized, and ultimately embraced/mimicked by fetishized labels? There are more concrete sides to this exploitation as well. One London-based Congolese woman explains the situation bluntly: “Sapeurs spend thousands of moneys just to put one outfit together but then they don’t have any house.”

The most boilerplate critique of Le Sape is that it reinforces a subservience to Western commodity and serves as a shallow imitative process. This is what Gondola defines as the dream and illusion of the Sapeur, “to conceal his social failure and to transform it into apparent victory. He dresses as if he were a CEO even though he is a janitor.” Moreover, “ The sapeur does not dress like a CEO imitate the CEO. He is a CEO, and if the sartorial writing is not immediately conveyed, he will learn the discourse required to convince others. He does not dress like (imitation), but as if (incarnation).”In 1999 Michaela Wrong interviewed a Sapeur named Colonel Jagger who claimed “If anything Sape has become part of the mainstream. It's been vulgarized. Government ministers wear couture and have Sapeur hairstyles. Just look at the Church pastors- even they now assert themselves”. In 2025 the Sapeur has been commodified, referenced, and integrated into a niche sect of pop culture numerous times. Sapeurs appear in music videos for SZA and Solange, they star in Budweiser commercials, high-profile European photographers seek them out to document them, and countless archive fashion accounts on social media repost their pictures. As well as Watanabe, Paul Smith designed an entire collection dedicated to Sapeurs.

Monica L Miller writes in her history and analysis of Black Dandyism that “dandyism’s current close ties to global capitalism may signal the death of or certainly a significant change in its ideological force (Roland Barthes’s axiom “Fashion killed dandyism” echoes here.)” Le Sape refashions and intimately styles brand names, but Le Sape is defined by the ability to refashion and combine them. How do those styles, the brands, and more generally, that sense of distinctiveness shift when Le Sape is globalized, and ultimately embraced/mimicked by fetishized labels? There are more concrete sides to this exploitation as well. One London-based Congolese woman explains the situation bluntly: “Sapeurs spend thousands of moneys just to put one outfit together but then they don’t have any house.”

The most boilerplate critique of Le Sape is that it reinforces a subservience to Western commodity and serves as a shallow imitative process. This is what Gondola defines as the dream and illusion of the Sapeur, “to conceal his social failure and to transform it into apparent victory. He dresses as if he were a CEO even though he is a janitor.” Moreover, “ The sapeur does not dress like a CEO imitate the CEO. He is a CEO, and if the sartorial writing is not immediately conveyed, he will learn the discourse required to convince others. He does not dress like (imitation), but as if (incarnation).”

That’s all for now!

Like what you’ve read? Once again: Zines are available for $15 at Casa Magazines NYC or for delivery! Direct all inquiries to my email at Bburton206@gmail.com