[minor Asteroid City spoilers within]

Writing about Wes Anderson is a sort of genre of its own. It is to enter a discourse never entirely directed at its subject, it is to unfurl more personal declarations on the nature of auteur, on self-consciousness hipsterdom, or on why we go to the movies. Anderson is seen as a focal point of reproducible auteurism, making him the target of cheap AI and terrific simplification. 2021’s The French Dispatch served as an explicitly stylized fantasy of time, place, and genre rooted in deep empathy for the recorders of a dizzying world. Asteroid City deploys Anderson’s characteristic style as a meta-stylistic stage to be subverted and more intimately explored. Some refer to Asteroid City as one of Anderson’s finest for this reason, others despise it for its indulgence in style and surface, but regardless the film seems to enunciate complete disregard for its cyclical discourse.

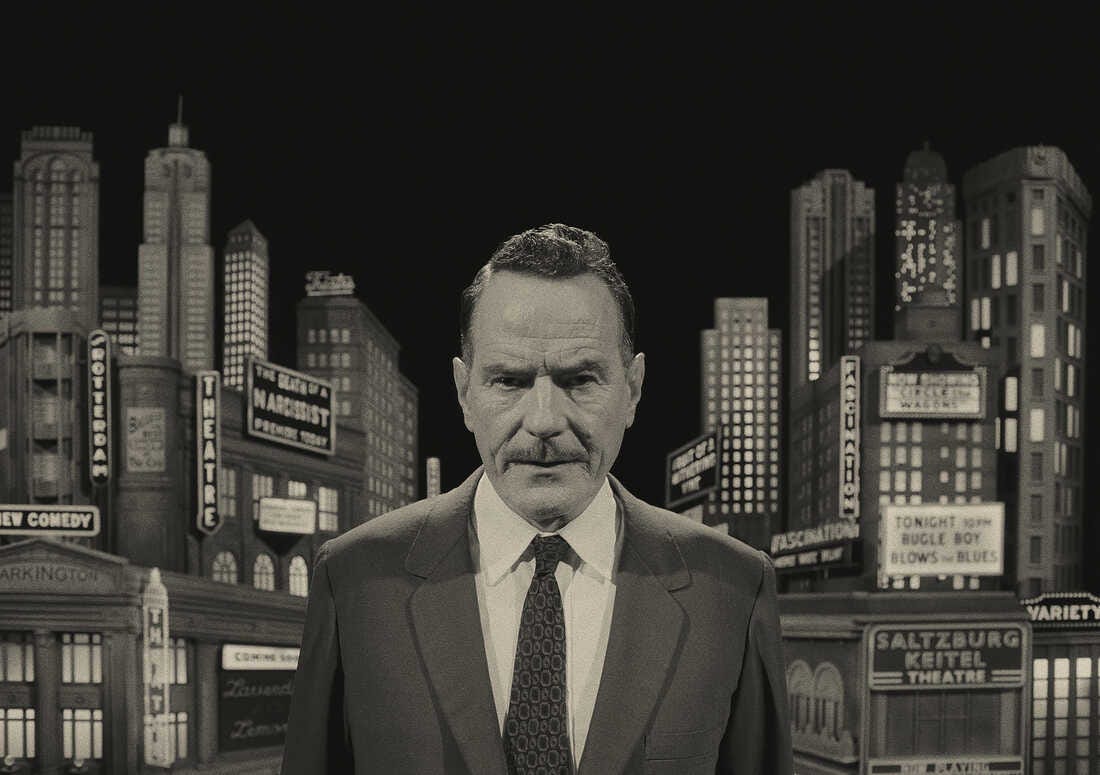

The ad campaigns, posters, billboards, and trailers define Asteroid City through bright colors, flat expanses, and twangy country warbles. The first trick the film pulls is an old one: Asteroid City is a play, the subject of a stark monochrome television program narrated by a solemn Brian Cranston. As we watch the play unfold Cranston chronicles the production of the work from varied standpoints, the fleeing actress, the heartbroken director, and the cryptic writer. These concocted slices of lore are no less arch or hyper-stylized than the play, but they directly question and stand separate from it. Unlike any of Anderson’s other metanarratives, these realities are engaged in discourse.

In this sense, Asteroid City is both a stylish sheen of bad fathers, precocious children, tidy Americana, and repression, and a reckoning with what it takes to make that kind of art. The play’s creators are heartbroken, they lash out at each other, and in slipping into the worlds of these broken stargazers they lose themselves. Creative expression is not escape, it is psychologically emptying. A central moment comes when Jason Schwartzman breaks character as Augie Steenbeck and tells his director (a devastatingly hot Adrien Brody), distraught, that after months of performance he still does not understand the play. His emotional attachment to his character seems unjustified without understanding, and he feels he must know what he has made. To the director, understanding doesn’t matter and the attachment Schwartzman’s actor feels is merely something to be used. It’s about telling the story, keeping the show running, and letting affect guide the meaning of obtuse art.

What emerges is not necessarily a creed for style against substance, nor is it really a kind of code for knowing Anderson. This is Anderson at his most theoretical - constructing a scenario and method of knowing and making work. Asteroid City tunes the emotional landscape of art production, to butcher the film’s language, it is to successfully enter a dream state - to ”sleep” and break with reality, entering wholly into the art.

Asteroid City is not so much an invitation to create, it is an invitation to be changed by art.

While old aesthetics battle for survival, new ones emerge.

After the sudden passing of Virgil Abloh, no one quite knew who could run Louis Vuitton menswear. The most talented designers in the menswear field were listed, yet none emerged. For a year seasons of recycled designs and a shallow guest designer passed as more and more lead designers and creative directors left their own houses. Then, a name appeared: Pharrell Williams

Immediately discourse erupted. Much of Abloh’s work already circled Pharrell’s, he brought back the Millionaire sunglasses Pharrell and Nigo developed with LV in the 2000s and he worked with Pharrell’s frequent collaborators, Nigo twice and Jacob the Jeweler. Was Pharrell fielded to reproduce an aesthetic Abloh had made so powerful and profitable? Design aside, some decried the decision to hire a celebrity, albeit one with decades of experience in fashion. Even with a name as legendary as Pharrell’s there was still a question of how anyone could design at his level or measure up to his legacy.

Louis Vuitton’s first menswear show with Pharrell as creative director was last Tuesday.

Pharrell’s focus seemed to be on plumbing the depths of his own legacy of garments. Behind the Louis Vuitton Damier check that defined his collection was a 2010 Billionaire Boys Club release focussed on “Digi“ camo pieces, now “pixelated“ via Damier. Varsity jackets from Pharrell’s high school are reproduced, more recent diamond Tiffany sunglasses are remade, and camouflage patterns, Pharrell’s favorite, abound. In a more direct recognition of nostalgia, Clipse walk the runway to an unheard track and Jay Z delivers a performance after the show. Elsewhere, Pharrell seems intent on honoring Abloh’s tenure with a new boat-shaped bag, an ode to Abloh’s many trompe l’oeil, and a ceremonial bag with a glass box so as to peek at a pair of LV sneakers Abloh designed for the house. Other than these brief nods and a very vocal sentiment that he is both student and a product of his collaborators and inner circle, this is Pharrell’s story.

And yet, a reference infers inevitable, albeit unfair comparison. A Virgil Abloh Vuitton show had a similar mastery of spectacle and luxury, of pieces referencing and deconstructing the late 90s/early 00s era of streetwear and hip hop, and of self-referential myth-making. Puppets on suits referenced 00’s Marc Jacobs era teddy bears, Ghanan heritage, and “characters“ who refracted LV through pop culture landscapes all at once. “Chess“ meant black and white Damier, hockey jerseys worn by the Wu Tang Clan, and armored “knights“. Here, there are fewer layers. Replicas and references are tidier, and metaphors of Point Neuf as bridge between Virginia and Paris are painted broadly. Williams’ Princess Anne High School varsity remains the same, yet bejeweled.

Williams’ goals are unmistakably different from Abloh’s, his goal is to honor the previous CD without succumbing solely to nostalgia. To compare these two is inevitable yet impossible. The artists are engaged with completely different subjects and goals. However, it is clear that Pharrell’s priorities were not to replicate the storytelling, worldbuilding, or avant bend of Virgil’s Vuitton.

On one hand, the fantasy is effective. There is a true sense of luxury, of fine craft, endless jewels, and “buttery“ leathers. There are sumptuous varsity jackets, baggy denim that spills over silky cargo socks (?), and million-dollar Croc skin bags with diamond locks and silver chains. Pharrell’s attention to product, his penchant for color and bold pattern, and a lifetime of trailblazing style inform what is ultimately a cohesive return of alluring luxury for Vuitton.

Williams’ appointment smacks of a board meeting on profit margins. He’s safe, reliable, and carries a celebrity allure. LV attempts to have its cake and eat it, supplanting opportunities to purchase replicas and entryways into Pharrell’s history and mythic past, while selling Abloh’s profitable sillouettes and motifs as “Pharrell-ized“ and therefore new. In other words, it is a new direction padded by early success, a plea for fans of Virgil’s work not to take their money elsewhere. Abloh’s LV sneakers are redone in croc skin in many colors and his beloved canvas of the varsity jacket is reproduced anew. Beyond the show’s reliance on Abloh to turn a profit,

As much as the show represented a strong aesthetic pivot, it also seemed to suggest a desire for the relevancy and profits of an older Vuitton, one that simply cannot be achieved through Pharrell’s new strategies and products. In accepting and admiring this new work, there is accepting a rhetorical numbing of what LV meant in culture for four years. Abloh and his work were unapologetically disruptive and paradigm shifting - Pharrell has not been hired to reproduce that disruption, but to effectively retain LV’s allure, and properly situate Abloh’s story in that allure. Accepting this is accepting the contradiction of Abloh’s motifs emptied of context and paraded as justifications of Pharrell’s work.

Some on Tik Tok claim that the reproduction of Wes Anderson’s aesthetic, the supposed hallmarks of a recognizable image, is as good as a Wes Anderson film. This strikes me as similar to those who input intellectual property for brands (usually Balenciaga) to “collaborate“ with via AI. By nature, both function in understanding “Balenciaga“ and “Star Wars“, “my trip to Providence“ and “Wes Anderson“ as fixed aesthetic entities. This philosophy sees medium as canvas, each equalized in their ability to express static ideas to be cycled and shuffled for eternity. The rise of the word content ironically signals that more is more, no matter what.

The difference between seeing film as a collection of static images or as a medium that can be bent, explored, and redefined reflects the priorities of standardizing and simplifying art. Anderson’s aesthetic is certainly recognizable (but certainly not completely uniform) but this does not guarantee critical or financial success for his films. Asteroid City was the biggest per theater opening since La La Land in 2016 in great part because it was not, aesthetically or discursively Isle of Dogs. Gucci which reigned as the most profitable and desired clothing brand for many years fired their immensely successful creative director and began churning out sentimental, pandering, broad shows in the interim. Gucci lost enough credibility that it now charts ninth in Lyst Index’s quarterly ranking of fashion’s most desirable brands. The nature of fandom at its broadest, of accepting or rejecting art wholly and without question (watching every Marvel whatever, buying the shirt solely because of the tag) accepts simple surfaces rather than the complex dimensional subversions art can offer.

I went to the theater last week and saw a film by William Greaves entitled Symbiopsychotaxiplasm Take One. The film takes a documentary style, filming the filming of a terrible scene of marital strife that its creators must continually improvise to make “good“. Each shoot is a repetition of this project. Greaves’ film is emptied of direction, yet there is constant conversation about what is controlled or intentional and what is not. It is at odds with its own lack of narrative or action, yet in its humor and discourse is described as one of the most accessible experimental films ever made. Its entertainment value is itself a mystery. Symbiopsychotaxiplasm Take One is a film that questions every aspect of cinematic surface and explores the ability of film and its production to be a discursive site.

Many take for granted the intuition and openness of an audience. The surface, the reproducible aesthetic, and the guaranteed profit are ephemeral and cheap. Audiences are noticing and responding, evidenced by Gucci’s fall to The Flash’s box office flop. Time will tell whether Pharrell’s first experiment in safe exploration of luxury is sustainable or increasingly meaningful. Asteroid City is already being defined as a knotty, successful, odd step for Anderson, a response to complicate and legitimize his experiments as more than simple gloss. Meanwhile, Greaves’ Symbiopsychotaxiplasm Take One plays to half full repertory screenings on a Sunday night, still inviting audiences to be changed and to discuss what it is they see.