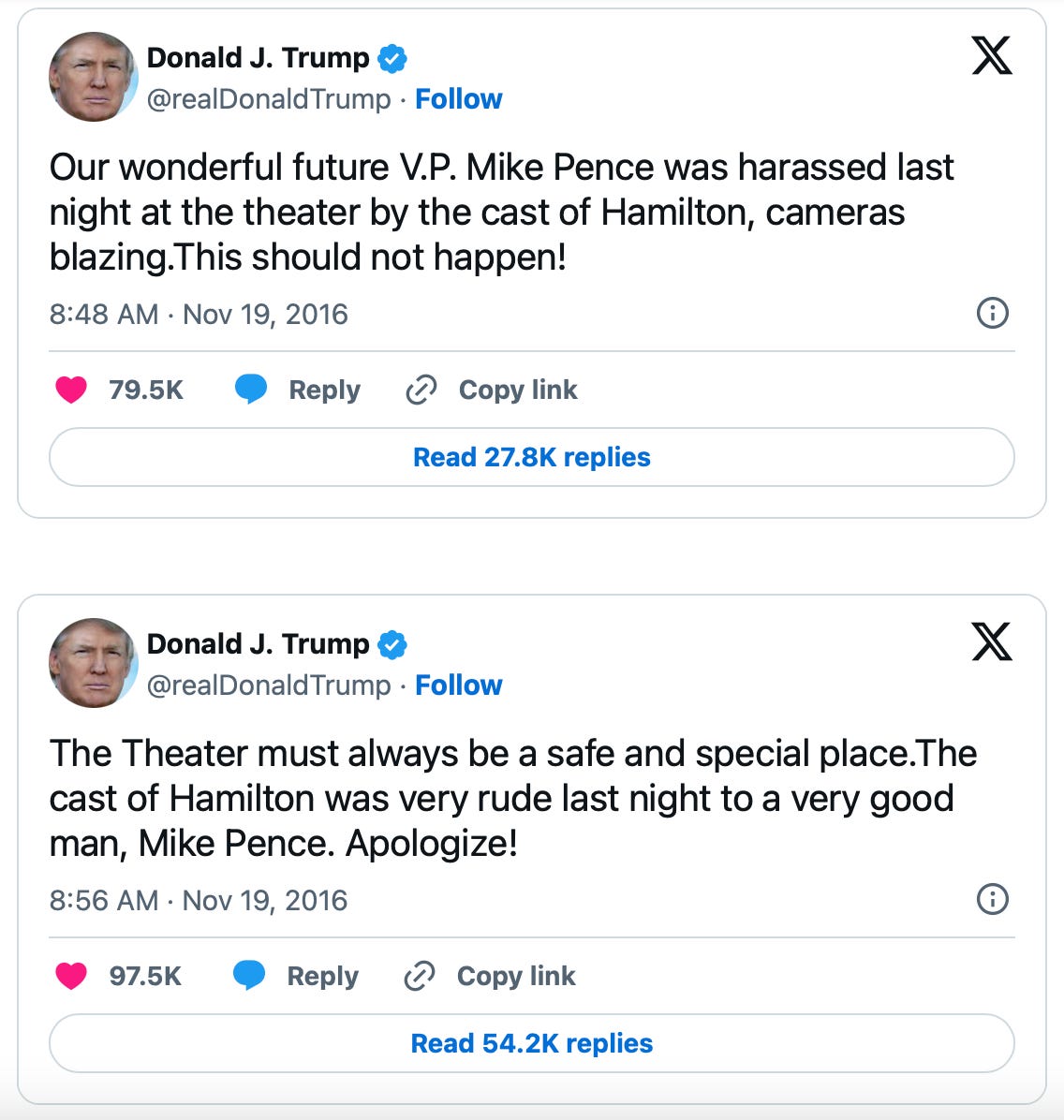

Brace for bad art. Bad theater, bad poetry, bad film. The fashion Twitter pick-me reposting Melania outfits remind me: bad fashion as well. I’m hearing less about the art responding to Reagan and more about the artists and audiences cut down by AIDS. I’m hearing about the worst slam poetry you’ve seen in your life. I’m hearing again about Trump-era Oscar wins. I’m hearing about Hamilton, the kind of Trump-era liberal jab Mike Pence could stomach. Art that warped history to make our country’s founding a myth again, something we could stomach.

I saw the headline for a Daily Mail article: “Joe Biden's 'lonely and lost' final days in office: Netflix binges, quiet tears and shunned by Kamala Harris' campaign.” In spite of the source, it all sounds more or less right, if not suggestible from publicly available footage. The exception is Netflix binges. What TV has the president been watching? What “binge” could possibly be soothing, if not invigorating him? Is this good for Netflix? Is this what Netflix, TV, art, is for?

I come into work the day after the election, that day my all black is a tired funerary symbol, almost indistinguishable from “fashion” all-black. I watch for eight hours as dozens if not hundreds of people stream into the department store where I work, unbothered, cheerful if not nonchalant, some grinning with a hollow ghoulishness. They flip through handbags worth thousands, assemble wardrobes worth tens of thousands, and attend Anglophilic tea ceremonies like their grandmothers. Today is a Wednesday to them, a day to shop. It’s not special. To this class, nothing will change. They boast safety and arrogant apathy through mindless consumption. One woman drawls that things are scary but they will persevere, she has just started reading Abraham Lincoln’s biography for inspiration. Her Chanel flats click against the marble as she wanders towards the Louboutins.

These headlines, pouting resignations, and retail therapy distractions reveal just why we can assume the art following a Trump election will be bad. It’s because art has been boxed in as a suppressive. This art soothes and distracts when we are abandoned by our vice president. It tells us what we want to hear to allow us to continue looking for four-figure-priced shoes. It is a masquerade to convince us our society is just. This is a model of consumption, of self blinding, of maintaining stasis. What can we excavate to soothe ourselves? What content is primed for pre-apocalypse moping?

The Trump/Biden era is defined by an increased class divide, the fall of nontraditional arts institutions, and their general standardization. It’s also defined by “content” - the homogenization of art production under the cruelty of industry, Wall Street valuation, and the algorithm. Work that functions as “content” is political because of its ability to evade responsibility to the present. “Content” numbs, stupefies, evades dissent from an algorithm representing our society’s worst impulses. The industrial pursuit of content in every medium keeps working/starving artists busy and reliant on exploitative mass mediums to survive. Even the art made in our modern system that rebukes “content” still lives in a little digital box on your streaming service between IP reboot slop.

Beyond criticisms of what this kind of art contains, I’ve seen incredible despair about the way our generations have become unable to stomach most mediums. We no longer read, we are too easily tricked by video editing, we cannot listen without watching. Another on Twitter makes the bold claim: the moving image is stupefying and dangerous. We are irresponsible with art’s power.

While in many cases “content“ is used to refer to published words or moving images, it also perfectly encapsulates fashion: art as pure product. Fashion’s industrial response to Trump was to celebrate the immigrant creators of its status quo, a pat on the back that the same systems that elected fascists could support (kind of) such diverse creators. Those seasons featured endless American flags, tattered, made into dresses, kitsch, anything. Even in irony, the hypersaturated stars and stripes became a grasp at rediscovering or owning patriotism - a way to sell America amidst distress.

The gut reaction from fashion has been split. The industry is wary if not attempting to remain on Trump’s good side, a concept that would disgust many young designers. However, a Trump economy will test their young businesses and force them to curb innovation and individuality with the commercial. The only way out is separatism, as designer Willy Chavarria puts eloquently: “There’s no longer any room for fashion to bring us to a place of fantasy, outside of reality.” Fashion (and art) can no longer be escapist for its own sake, product for its own sake, fantasy for its own sake. This is how art becomes a luxurious numbing agent, a guiltless escape. The only way fashion/art works as fantasy is if that fantasy is about generating a new, empowering reality.

In considering all the ways art can dangerously “stupefy,” I wonder if there is also a way for art to dangerously rouse. I’m talking about art that imagines futures for us so as not to allow us escape, but that offers us steps. Instead of creating in tribute to banned and censored work, why not create work worth banning, fearing, reading? I’ll leave it at this: some of the most powerful films I’ve seen in the last five years came with an FBI warning. The best clothes have not been on Vogue Runway's front pages. Remember when plays could cause riots? If we are to talk about art in times of repression, maybe this is what we should mean.

This is the kind of art that, like subterfuge or protest, must exist outside of the arts industry structures that ensure that “revolutionary art” will not be effective. No, I want degenerate, impossible, sublime, instructive, unalgorithmic, unsafe art. Instead of Hamilton, I want to experience something that would make Mike Pence not just frown, but actively call the cops.

We should not expect an arts renaissance to materialize - we do not have the social or economic landscape for it to do so. Instead, we must work towards a new kind of art production and distribution that can be directly tied to movements for a better world. This is more than existential for society, it is existential for human existence. I have not forgotten the cynicism of Paul Schrader, who, at a Q&A, doubted that film would be around in a hundred years. We must ensure it will be.