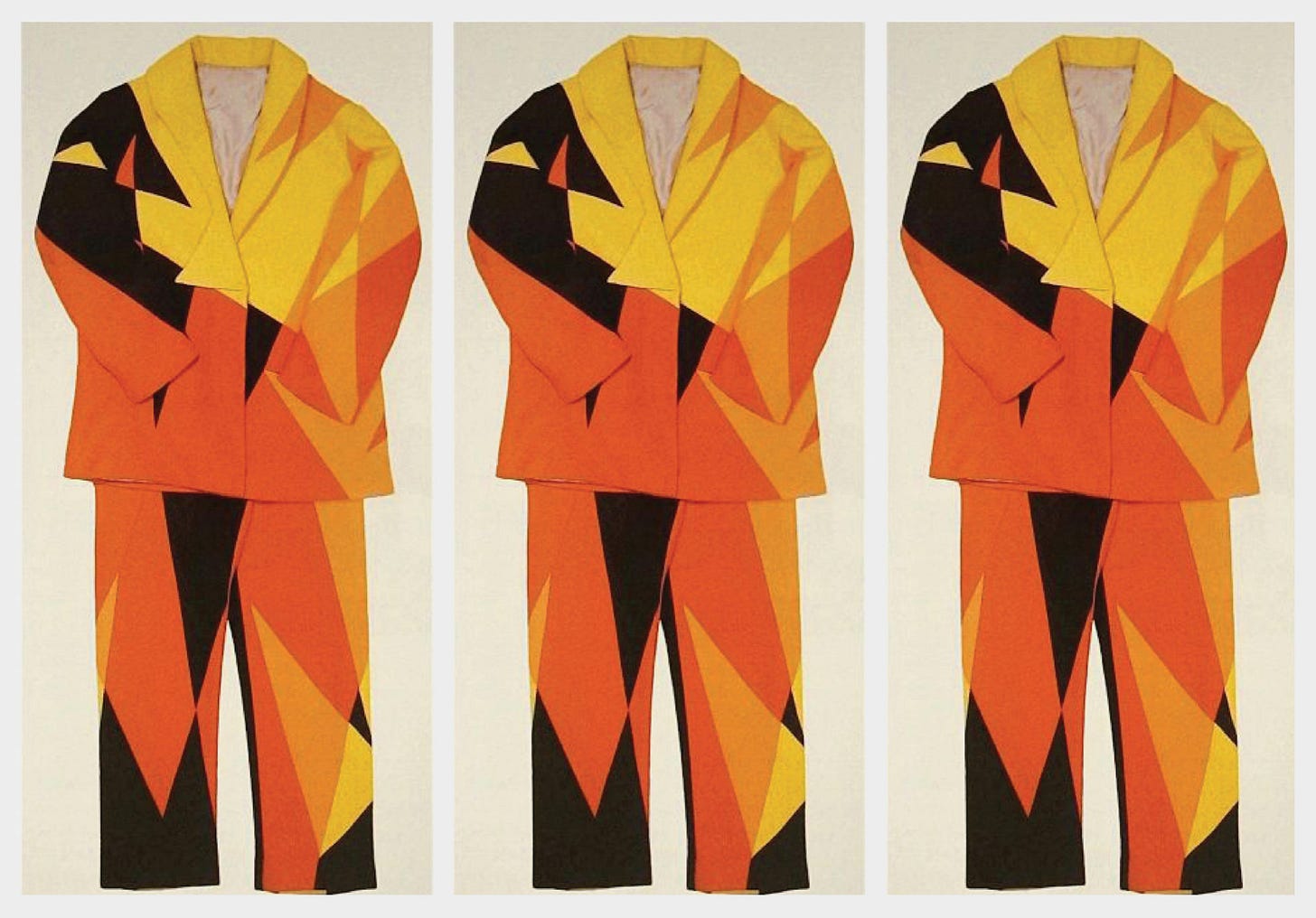

Looking at a suit by Giacomo Balla today is a fascinating thing. It is an example from a time in which intellectualism and charged philosophies combined with the commercial world to create clashing, experimental, and thought-provoking pieces of design. It’s a way of producing that feels foreign and utopian to a Gen Z cynic - a way of producing that feels authentic and exploratory.

Balla was a futurist, and the designs of both him and his peers are often used as abstract inspiration for Italian fashion houses like Prada and Missoni. The garments he designed are defined as futurist not simply because Balla was a futurist, but because of a formal manifesto1 connected to his work. He writes:

WE MUST DESTROY ALL PASSÉIST CLOTHES, and everything about them which is tight-fitting, colourless, funereal, decadent, boring and unhygienic. As far as materials are concerned, we must abolish: wishy-washy, pretty-pretty, gloomy, and neutral colours, along with patterns composed of lines, checks and spots.

WE MUST INVENT FUTURIST CLOTHES, hap-hap-hap-hap-happy clothes, daring clothes with brilliant colours and dynamic lines. They must be simple, and above all they must be made to last for a short time only in order to encourage industrial activity and to provide constant and novel enjoyment for our bodies. USE materials with forceful MUSCULAR colours - the reddest of reds, the most purple of purples, the greenest of greens, intense yellows, orange, vermilion - and SKELETON tones of white, grey and black. And we must invent dynamic designs to go with them and express them in equally dynamic shapes: triangles, cones, spirals, ellipses, circles, etc.

It seems to make sense. Balla proposes a futurist suit, his suit fits the qualifications he sets out, and thus the suit is a “futurist suit“. However, there is a subtext to Balla’s suit that does not change its futurism but adds something to it. Eloise Hawser analyzes Balla’s suit in the context of greater Italian politics and futurist trends and notes the nationalist tendencies of Balla. The futurists fight against aesthetic neutrality and in the name of brightness and affect transform into a more political philosophy specifically embraced by Mussolini. Hawser applies this application of Fascist politics to the suit by writing that “On the one hand, the Futurist suit is designed to incite chauvinism, violence, and warfare. On the other, it is so lightweight and dandyish that it fails to withstand its first public outing, being shredded by a ruckus with students.” The suit’s futurism does not disappear but becomes a supplement to the suit’s fascist elements.

Just because a garment (or art object for that matter) is tied directly to a theory does not make it subservient to or exclusively defined by that theory. Wearing is what defines and activates the political/philosophical power of a garment; It is only a Futurist garment if it can be worn, worn out, and enunciate emotional shock, and it can only be a Fascist garment if its presence incites violence, nationalism, and chauvinism. The modern experience with Balla’s suit has little trace of its original Fascism, however, it reveals the way in which the assignment of theory to garment is in complete flux. Fascist clothing is not simply based around static insignias or uniforms - it can be reborn in the garment with new, sometimes inscrutable lives

I really don’t want to write about Ye. Each statement and statement-garment made in the last few months seems so focused on reaction, and attention, that to write more about him would be fulfilling its warped goal. I do so now only to take seriously the threat of a powerful aesthetic tastemaker aligning himself with historical and modern iterations of fascist ideology.

There is a fascinating question his ideologies have spurred, that many materialistic and disturbingly self-serious hypebeasts have agonized over: What do Yeezy’s mean now? What to do with the endless sneakers, the old tee shirts resold for thousands, and the many many clothes and shoes connected with a now fractured identity? Is the original philosophy of Yeezy retained, or has it transformed into a new object emblematic of Ye’s beliefs? Whether one can listen to Ye is different - this seems a more private exercise defined by one’s ability to separate art from the artist. This question concerns the garment, which melds with one’s body, signifies and speaks, and becomes an extension of one’s self. These hypebeasts want to know if retaining an alliance to Ye’s design, they align themselves with fascism.

I think this is a question that is self-consciously asked. What, or rather who, else does Yeezy point to? When asked in a community of hypebeasts who all know who Ye is and what his philosophies are, how can the meaning of the shoes designed under his name signal anyone else? People do not always purchase an item because of the item itself - the associations it creates may be to a greater ideal. A bag may gesture to but not actually be a Gucci Jackie Bag. A Supreme tee shirt may imply a box logo shirt ten times the price, and a Yeezy 750 may invoke the original influence of the 350. In contemporary culture, both Yeezys reflect Ye then, and the infamous white lives matter tee shirt.

This is not to say that these two garments function the same. The Yeezy 350 represents a re-contextualizing of an old garment through new facets of a signifier, whereas the shirt represents something new - the gateway of a new theory (alt-right thought, white supremacy, quasi-fascism) into an older Yeezy aesthetic. Ye is important here not because of his own work, but because of what the work he heightens and molds together comes to represent, or maybe always represented.

In a year Ye spent millions on Balenciaga. Demna, the head designer of the house, essentially designed his Gap collaborations and Donda merch. Balenciaga was one of the most financially successful brands in the last few years, surpassing Michele’s Gucci on at least one occasion. The influence of the Balenciaga aesthetic advertised by Ye and the Kardashians, rappers coming through the Donda sessions told only to wear the brand, and countless other celebrity endorsements have cemented its influence. Take this example of a short back-and-forth on Twitter.

The aesthetic is loose, being appropriated by couture and fast fashion alike. Now, many of its silhouettes and garments are connected to a man who has spouted white supremacist and fascist sympathy. Are these designs inherently tainted? Has fascism “infected” them? If we recognize that Demna’s designs through Yeezy/Gap and Balenciaga have significant cultural and aesthetic staying power, what can we say about his work more than his connection with Ye?

Demna is fascinated with the future. Many of his runway presentations feature imagery that appropriates and warps fears of various climate crises. Vicious snowstorms, muddy wastelands, and UN halls. His clothes are distressed and deconstructed, ripped and mixed, thick leather and harsh denim. Faces are often masked or covered and skin is tightly bound in BDSM latexes and leathers. Boots are chunky and tactical, sneakers are odd and technical. Each ensemble seems to aesthetically declare that the wearer is ready for the apocalypse.

Amidst all the primping and preening over dehumanizing leather, steel, and stocking couture, Demna also heavily brands Balenciaga within the very capitalistic hellscape that causes the disasters he references. This year it was Adidas before it was Gucci, and even earlier it was with Vetements’ at the time mind-boggling luxury hoodies. With the bootleg stall as his base, good taste seems to dissipate as “Balenciaga“ is slapped onto anything from a T-shirt supporting Ukraine to a flip of an FBI hoodie. When this world meets Demna’s couture in perfect contradiction his world congeals. His obsession with the homeless crystallizes into multi-thousand dollar leather garbage bags and Lays bags, and deconstruction becomes an ethically questionable spectacle and hollowness.

Demna is positioned to indulge endlessly in crazed fashion capitalism and point shakily at the incoming end times, yet seeming only to offer nihilism, sex, and the opportunity to hide one’s face behind shining cobranded masks. What does it mean when, in “anticipation of the future”, Demna offers the rich a pre-annihilated product meant to aestheticize poverty at exorbitant prices? When Demna references a nuclear winter or an incoming flood, does the wearer/viewer/designer consider how his clothes may be worn in a hurricane? Is Demna revealing his overpriced Balenciaga x Adidas collaboration in the New York Stock exchange supposed to be ironic or thought-provoking? What does it say other than to parade capitalistic consumption within its very halls?

It is an inverse of the futurist manifesto in its colorlessness, but similar in its promise that the garment can serve as a masculine tool, a means for increasing capitalist consumption, and a force of blunt aggression against “neutrality“. It is a philosophy of design focussed on violent reactions, not dissimilar to Ye’s recent garments.

Ye’s interpretation of Demna’s world is troubling. He articulates Demna’s obsession with poverty in literal terms while simultaneously promising utopian communities with free clothes and Ye-designed cityscapes. Compare this to the Billionaire philosophy focused on utopian space escape from Earth and the promise of new utopias based on cults of personality, and Balenciaga becomes a uniform for individualist bourgeois escape from reality.

In Ye’s interview with Alex Jones in which he professes his love for Hitler and Nazi aesthetics, he dons a 2019 Vetements motorcycle jacket and a skintight mask. He looks like a model in one of Demna’s shows (he was, after all). And in that moment, the professing of Fascist ideology becomes directly bound with a garment and ensemble inspired by Demna.

Much has been written about the various Nazi/white supremacist dog whistle symbols in memes, clothing, and blogospheres. The militant garbs of hyper-nationalist groups are as simple in their signification as tea party appropriations of Revolutionary war symbology. The power of these aesthetics is outlined succinctly by William Westermeyer:

Social movements are not only aggregations of people acting toward political ends, but they are also producers of what Stuart Hall (1982) called “signifying practice”—they create meanings and establish articulations between concerns, ideology, and action. In another sense, they “order” or figure ideas, people, and history, which in turn help build commitment and participants’ sense of empowerment.2

While Demna’s work may not be intrinsically Fascist, it is certainly interesting that his aesthetic is built through a meme-adjacent form of streetwear flipping and internet humor, military aesthetics, an obsession with the apocalypse, and hollow anti-authoritarianism. What does one do with the emergent similarities between quasi-fascist ideology and warped feudal utopianism in Demna’s world? Disturbingly, it seems as though through association with Fascists and the construction of such open and reactionary politics, Demna has created garments that could potentially serve as adept vehicles for Fascist ideology.

Due to a separate incident involving the sexualizing of adolescents and the invocation of anti-child-pornography laws, many wonder if Demna will remain at Balenciaga. Notably, while Balenciaga has distanced itself from Ye, Demna has made no personal statements. Ye posted texts between the two less than a month ago.

As a Jew, I am obviously sensitive to the history of the Holocaust and European pogroms. What were the signs that my relatives saw that convinced them danger was near? What do you see, and how do you interpret what you see to know you must take action?

For this reason, I consider these issues of creeping and popularizing aesthetics that popularize and communicate fascism seriously. If you look at the way hypebeasts, sneaker collectors, and fan communities react to these scandals, you may find that their aesthetics are powerful enough to work. After all, it has been enough to power a whole new sect of antisemitic and fascist thought with new energy. I end with a quote from a book that has taken my mind off of this terrifying, evolving world. It cements a powerful yet dangerous skill acquired as a Jew, an English major, and a fashion nerd: paranoia.

[He] had treated paranoia as if it were something that could be domesticated and trained. Like someone who’d learned how best to cope with chronic illness, he never allowed himself to think of paranoia as an aspect of self. It was there, constantly and intimately, and he relied on it professionally, but he wouldn’t allow it to spread, become jungle. He cultivated it on its own special plot, and checked it daily for news it might bring: hunches, lateralisms, frank anomalies.

…But he was also fond of saying, at other times, that even paranoid schizophrenics have enemies.

-William Gibson, Pattern Recognition

https://www.readingdesign.org/futurist-manifesto-mens-clothing

https://polarjournal.org/2022/08/30/theyre-spinning-in-their-graves-art-ordering-history-in-the-tea-party-movement/